Hay una sensación que nos anticipa un acontecimiento excepcional. La

impresión de que algo está a punto de suceder. Puede que sea algo

pequeño, un chispazo. O algo de proporciones estratosféricas. La

inminencia se ha colado en el discurso del arte contemporáneo como

palabra clave para acercarse a lo que identifica su cualidad

diferenciadora. Sin ir más lejos, La inminencia de las poéticas fue el título elegido por el comisario de la actual 30ª Bienal de São Paulo. En su nuevo ensayo, La sociedad sin relato. Antropología y estética de la inminencia,

el filósofo y sociólogo del arte Néstor García Canclini (La Plata,

Argentina, 1939) se acerca a una serie de artistas latinoamericanos e

indaga a través de sus obras la forma en la que el arte contemporáneo da

respuestas a algunas de las grandes preguntas que las ciencias sociales

no consiguen ya responder.

Pregunta. En su ensayo introduce ideas como la de la

“inminencia”. ¿El sentido que le da en el contexto del arte

contemporáneo está relacionado con ese descubrimiento personal e íntimo

que tenemos, por ejemplo, ante una metáfora que nos abre a la percepción

o comprensión de algo? ¿Con cierto sentido de lo que llamamos

“poético”?

Respuesta. Tomé la noción de inminencia de Borges,

en ese texto donde habla del hecho estético como la inminencia de una

revelación. Y me puse a explorar antecedentes, yo había hecho mi tesis

sobre Merleau-Ponty, y me acuerdo de algunas nociones próximas y de la

misma noción de inminencia del mundo, de la que habla Merleau al

analizar el arte de su época. También revisé la noción de aura de Walter

Benjamin y encontré muchos artistas y críticos contemporáneos que

usaban ese término. Me pareció que había un linaje que estaba diciendo

algo sobre el arte como modo de pensar las imágenes, pero las imágenes

que no son definitivas. Hablan de lo no resuelto, del conflicto abierto,

que quizá sea una de las pocas diferencias que le queda al arte en

relación con los medios masivos, con otro tipo de imágenes publicitarias

o que están sometidas a una legalidad y obsolescencia del mercado.

P. ¿Sigue teniendo el artista el papel de

propiciador de esta “inminencia de una revelación”, de mensajero, del

genio concebido en el romanticismo?

R. No faltan artistas que lo interpretan en esa

dirección y les encanta tener ese papel de anticipadores. En rigor, no

es así. Me parece que lo que uno observa en el arte contemporáneo son

capacidades peculiares en los que se llaman artistas para actuar en

intersecciones donde las imágenes cruzan sus sentidos de muchas maneras.

Me parece que la idea de genio ya no se la cree casi nadie. Pero lo que

sí permanece de la modernidad es el énfasis en la originalidad. No hay

nada peor que le puedas decir a un artista que el que eso ya lo has

visto antes. Y, en rigor, todos saben que actúan en un mundo de imágenes

muy interconectadas, más aún desde Internet. Y que es difícil inaugurar

algo enteramente. Actuamos en el cruce y buscando generar una

intersección sorprendente, el asombro lo buscamos no en la originalidad

de los objetos o en el trazado de una imagen sino en la composición de

elementos o en la desposesión, al aislar un elemento que antes estaba en

otro contexto.

P. Después del posmodernismo, ¿hay una nueva

revisión del modernismo? Me refiero a las ideas de Andreas Huyssen de

volver un paso más atrás para comprender lo que nos dejamos en el camino

sin conocerlo a fondo. En su libro, usted dice: ni posmoderno, ni

pospolítico, ni posautónomo.

R. En realidad eso lo trabajé más en otro libro, que

es Culturas híbridas, en el momento caliente de la relación

modernidad-posmodernidad. Quería oponerme al carácter disyuntivo que

hacía del posmodernismo, de hecho, una nueva vanguardia a pesar de que

criticaba la noción de vanguardia. Hoy estamos viviendo una crisis de la

modernidad. En Europa, en América Latina, en Estados Unidos y en los

países protagonistas de la modernidad. Una crisis de la modernidad

económica, al subordinarse lo social a lo económico y lo económico a lo

financiero, y redefinir lo que se entendía por lucro, por intercambio,

por acumulación, así como el sentido social de las prácticas. Me parece

que es necesario recuperar esa amplitud de las cuestiones para no caer

en la ingenuidad de que todo se trata de equilibrios financieros. Y en

lo cultural también, se agotó claramente el proyecto más naif de la

modernidad, que era un proyecto teleológico que creía ir a una

culminación de todas las culturas en una sola historia, que se iba a

parecer obviamente a la occidental. Hoy es demasiado evidente que hay

una pluralidad de historias que no se pueden subsumir una en otra, pero

se ha acrecentado la necesidad de ver cómo conviven las culturas en una

interdependencia global tan acentuada. Y lo que sucede en The Factory,

en Beijing, tiene una resonancia en lo que sucede en el SoHo de Nueva

York y a su vez en la escena artística de São Paulo. Me parece que el

arte es un lugar bueno para pensar, que estimula a reconsiderar

justamente los lugares comunes porque su intento insistente es salirse

de esos lugares. Todo se hace dentro de un encuadre que yo sigo viendo

básicamente moderno. Diría más, así como pasamos hace unos años de la

hegemonía del posmodernismo a la hegemonía del pensamiento sobre la

globalización, todo eso que ha sedimentado nos lleva hoy a una discusión

sobre la crisis del capitalismo y las relaciones entre capitalismo y

cultura.

P. En el campo cultural y específicamente en el del

arte contemporáneo es evidente esa descentralización, esa

deslocalización y, algo que se dice también en el libro, es que ningún

artista se siente solo de su país de origen. El encuadre dentro de

cierto nacionalismo es algo ajeno a la actitud del artista de hoy.

R. Hace tiempo que terminó la época de los

pasaportes artísticos, aunque todavía a veces a los artistas

latinoamericanos se les pide que representen su supuesta identidad. Pero

los artistas más destacados de Latinoamérica, Gabriel Orozco o Guillermo Kuitca,

podrían estar haciendo su obra en otros países. De hecho, Orozco tiene

estudio en Nueva York, en París y en México, y sobre todo en los últimos

años el pensamiento japonés está más vivo en su visualidad que el

occidental. Es un ir y venir entre culturas tomadas muy libremente, pero

no solo porque los artistas viajan mucho más y los comisarios también,

sino porque los recibimos en nuestra casa en nuestro ordenador.

P. Quizá lo más importante de este libro es el papel

que le da a los propios artistas, por encima de teorías demasiado

complejas. El interés de ver con mayor atención las obras. El artista,

que es a veces el más olvidado al hablar de todo el eje y el sistema del

arte.

R. Para mí esto fue una novedad en este libro porque

hasta ahora había trabajado mucho en sociología del arte, haciendo

estudios de públicos, de mediadores, de la crítica, y me di cuenta de

que —de acuerdo con mi vocación antropológica— tenía que escuchar a los

artistas. Ir a sus talleres, a sus lugares de exposición —de las

galerías a las bienales— y ver qué sucedía en cada lugar. Escuchar al

artista en distintas situaciones porque actúan de maneras diferentes, y

lo que el artista dice, básicamente lo dice a través de la obra. Lo

demás puede modificar el sentido de la obra o influir en las maneras de

su recepción, pero las obras, aunque sean efímeras como una performance,

son documentos culturales que deben ser tomados en cuenta a partir de

la enunciación. No hay conceptualización de ningún curador que pueda

anular la elocuencia enunciadora de una pintura o de una instalación o

una performance. Entonces la primera actividad necesaria, y no solo para

el antropólogo, es escuchar al artista y permitir que su obra, más que

él mismo, diga lo que pretende enunciar.

P. Todos los artistas que ha elegido para este libro

trabajan dentro de lo que se considera arte conceptual. ¿Considera que

la obra sin el desarrollo privilegiado de un concepto que la sostenga es

menos interesante?

R. Me cuesta pensar en obras que no tengan un

concepto detrás. Pueden ser conceptos no explícitos, que no traten de

imponerse a las imágenes, en el sentido en que Lévi-Strauss decía que la

ciencia no es tan distinta de la magia, lo que pasa es que la magia

tiene un conocimiento sumergido en imágenes. Todo arte ha sido

conceptual, lo que ha ocurrido a mediados del siglo XX es que hay un

predominio de la elocución semiótica sobre la exhibición y el juego con

la imagen. No en todos, y además los artistas que elegí recogen esa

tradición conceptualizante de maneras diferentes, mucho más poética en Carlos Amorales o en Gabriel Orozco, más conceptual en Antoni Muntadas y Santiago Sierra.

Más individual en artistas como Orozco y Amorales, más colectiva como

reconocimiento de la fuente creativa, a veces como trabajo efectivo en

grupo, en el caso de León Ferrari y de Teresa Margolles,

o el propio Muntadas. Son modos distintos de inserción social y de

reconocimiento del grado en el que la articulación de concepto e imagen

en la obra procede de un cierto contexto.

P. ¿La crítica de arte tiene un papel distinto ahora con respecto a esa necesidad de ordenación, de clasificación, categorización?

R. Aunque sigue existiendo la crítica como glosa

literaria de lo que la obra estaría diciendo, cada vez más los críticos

se forman en varias profesiones a la vez. Saben de museografía, de

filosofía, de antropología, pueden ser curadores porque entienden mucho

más que la obra aislada. Ser crítico hoy es estar en la intersección de

varias disciplinas. Como, en realidad, se tiene que ser en cualquier

otra disciplina. No se puede ser antropólogo solo en la forma en que

clásicamente lo dijeron Boas o Lévi-Strauss.

13/12/12

19/11/12

7/11/12

The structures of art. An interview with Mario García Torres MONTSE BADIA ; 2012

Mario García Torres works with very specific elements (hidden

stories, rumours or un-clarified details) from the history of art, film,

other artists, events from the past, etc. These investigations

transform into stories that can take the form of diaporamas, videos,

books, curated exhibitions or postcards, to mention just a few of the

possibilities. Underlining a stance between critical and poetic that

vindicates the element of the subjective, in the following interview,

Mario García Torres talks about the reasons for choosing his formats for

production and presentation, his relation with the Internet and the

structures of art, and his negotiated comfort with the art system.

Montse Badia: In your projects there is a diversity regarding forms of production/presentation/distribution. I’m thinking of two examples: “Alguna vez has visto la nieve caer” (Have you ever seen snow) (2010), a piece in which, on the one hand, all the research into Hotel One and Kabul has been carried out from your home computer, via the Internet, without the need to travel to Afghanistan, and on the other, the interesting feature that it is a diaporama, that could also function as a narrative. Another case: is your exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, where you intervened in the bookshop, inserting postcards into some of the books. I would like to know how you decide the form or channel for presentation that you use for each one of your pieces.

Mario García Torres: My practice is not defined by my commitment or development of a medium. Each project has a distinct nature and the medium in which each aesthetic transaction is distributed is governed, in my point of view, by being the most efficient depending on its nature. My work in general explores the structures of art and the way in which these structures make possible this thing that we call art. My approach ranges from historical investigations into the practice of other artists to personal and intimate reflections about the negotiation of my practice in the art system. As you mentioned, "Alguna vez..." and the intervention in the bookshop at the Jeu de Paume are very different in nature. The first is the result of a long investigation –it is worth noting one not done exclusively on the computer– into the history of Boetti in Afghanistan, and specifically the hotel that he managed in Kabul during the seventies. The intervention in the Jeu de Paume was the extension of another project – the ones that I call more personal, intimate and immediate, the majority of which take place in the studio – one that I have now been doing for several years. It consists of each time I go on a work trip and find myself in a hotel where there are sheets of headed notepaper, I sit down for a moment and reflect about what I have done as an artist, as well as the future of my work, and I write a promise on the paper. It is more or less always the same phrase, a version of: “ I promise to give the best of myself in the years to come”. There must be forty or fifty of these sheets in existence and the project that continues today, consists of a collection of these promises. This project exists as I’ve described it, but also in a musical form – the explanation of the project became the words for a song that I commissioned from a musician friend, Mario López Landa – and a number of postcards, illustrating the modes of transport (airplanes, boats, buses) that had taken me to work, on which I had written the same phrase were distributed in the bookshop of the Jeu de Paume. I aimed for the discovery of these postcards to be a surprise, and not on the wall as is customary, in the way that the headed sheets are exhibited.

MB: To investigate the structures of art sometimes you develop projects, books or curate exhibitions. In the case of the show "Objetos para un rato de inercia" (Objects for a moment of inertia), that took place in the Elba Benítez gallery in Madrid and which brought together works by David Askevold, Alighiero e Boetti, Luis Camnitzer, Barry Le Va and Francesc Torres. The declaration of principles was clear: "History, despite its insistence on the contrary, pertains to the present. History is always being made. It is a process not a result. History, and the writing of History, are one and the same thing." Is it a way of activating propositions that took place in the past, of which only the record or narrations are left? Do the historic investigations serve to understand the present better?

MGT: Definitely. If it wasn´t for the fact that I believe that each historic narrative, that I use as an excuse to generate another narrative, didn´t have an impact on our contemporaneity their wouldn´t be any reason to use them. In this sense, my initiatives are a conversation between my personal interests, with the understanding that I do them through a subjectivity that is situated in the present, as well as an interest in the more complex range of art that makes it possible for my work to exist. In this sense, it’s not just me as a person that activates these narratives, but a more complex system that supports the need for this revision.

MB: Your works function perfectly as stories, you meticulously investigate events, details about other artists’ projects, rumours and from there elaborate a history, a story in which the objective data and your interpretation coexist, sometimes endowed with a certain poetics. What is your stance in relation to more recent art history, to what is told, what is omitted and what is very superficially explained?

MGT: My pieces are very personal narratives that have to do with sharing my own experiences, desire or interest in a specific history. In this sense I see it as a way of making history, though very different from the one that pretends to tell the truth. Perhaps my narratives function as complements to those more official ones, as it is these details that are omitted that, most of the time, catch my attention.

MB: What is your working methodology?

MGT: When a piece is exhibited, a long time has passed from the moment when the episode in question excited me. The majority of times I begin an investigation, not very methodologically, about something that interests me and afterwards, at some point, I see the potential for it to convert into something that would be interesting to recount more publicly. The majority of times I rely on these things that have drawn my attention, the notes in a box on my desk and, little by little, different invitations end up also defining which ones are made and presented in specific temporal or geographic situations.

MB: What are the main points of confluence and also differences between your role as an artist and when you expand it on occasion to become curator of exhibitions?

MGT: To me there don’t seem to be that many differences. I am an artist, and my interventions as a curator have to do with looking for a different way of sharing my interests. Sometimes it can seem more to the point to make an exhibition that tells the story in a more personal manner, hence the exhibitions. But in reality I see it all as a single body of work.

MB: You often cite works or parts of work that are already made to begin your own process. Would you allow your works also to become the object of citations, appropriations, re-enactments or revisions?

MGT: It would be an honour if somebody one day saw them this way, and would continue these narratives, in whatever manner, to know that in some place in the world someone might continue to be interested. In the end, one works just for this to find people who have similar interests. I think that in the end my work comes down to this.

MB: Are you concerned about the notion of truth? Do you think that truth is possible in art?

MGT: No, I have absolutely no interest.

MB: What is your relation with the Internet, for you, is it a tool for research, communication or dissemination?

MGT: Obviously it is always my first point of contact with a subject and many times it leads me to investigate things in a less methodological way, a richer way. It situates normal people, everyday people, at the same level as books and official sources. Internet is present all the time, and I don´t blame it for often being wrong. I like it. What better way to divert an investigation towards something contradictory or further from the truth. It is there that one finds relations that potentially become something interesting, in the weaving of a new way of telling a story.

MB: Many of the works that you make at present could be disseminated perfectly via the Internet however they tend to be shown within the parameters of the institution. Have you ever thought about sometimes using the possibility of other routes to show and distribute your work?

MGT: I’ve never thought about it in depth. I believe that in the end I’m interested in the experiential part of art however contradictory that might seem. The use of films and slides, for example, has to do with having a cinematic experience, which would be lost if it was seen on a small monitor. I believe that there are pieces that can be disseminated on the Internet, but not the majority of mine. I am as concerned about the experience, as about the data within them.

MB: Do you think that the institutional framework (museums, art centres and also big events like Documenta or international biennales) is flexible and does it adapt to the new needs required by artistic practices?

MGT: Yes, it doesn’t trouble me. I believe that I have constantly tried to use this framework to talk about what I want to. Obviously there are limitations, but there is also a lot of flexibility. I believe that up until now, each time they have invited me to exhibit in a biennale or an exhibition of this type, I have ended up doing my work elsewhere. For me the work exists where it is executed and not where it is exhibited. That’s the least of it.

From A-Desk.

Montse Badia: In your projects there is a diversity regarding forms of production/presentation/distribution. I’m thinking of two examples: “Alguna vez has visto la nieve caer” (Have you ever seen snow) (2010), a piece in which, on the one hand, all the research into Hotel One and Kabul has been carried out from your home computer, via the Internet, without the need to travel to Afghanistan, and on the other, the interesting feature that it is a diaporama, that could also function as a narrative. Another case: is your exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, where you intervened in the bookshop, inserting postcards into some of the books. I would like to know how you decide the form or channel for presentation that you use for each one of your pieces.

Mario García Torres: My practice is not defined by my commitment or development of a medium. Each project has a distinct nature and the medium in which each aesthetic transaction is distributed is governed, in my point of view, by being the most efficient depending on its nature. My work in general explores the structures of art and the way in which these structures make possible this thing that we call art. My approach ranges from historical investigations into the practice of other artists to personal and intimate reflections about the negotiation of my practice in the art system. As you mentioned, "Alguna vez..." and the intervention in the bookshop at the Jeu de Paume are very different in nature. The first is the result of a long investigation –it is worth noting one not done exclusively on the computer– into the history of Boetti in Afghanistan, and specifically the hotel that he managed in Kabul during the seventies. The intervention in the Jeu de Paume was the extension of another project – the ones that I call more personal, intimate and immediate, the majority of which take place in the studio – one that I have now been doing for several years. It consists of each time I go on a work trip and find myself in a hotel where there are sheets of headed notepaper, I sit down for a moment and reflect about what I have done as an artist, as well as the future of my work, and I write a promise on the paper. It is more or less always the same phrase, a version of: “ I promise to give the best of myself in the years to come”. There must be forty or fifty of these sheets in existence and the project that continues today, consists of a collection of these promises. This project exists as I’ve described it, but also in a musical form – the explanation of the project became the words for a song that I commissioned from a musician friend, Mario López Landa – and a number of postcards, illustrating the modes of transport (airplanes, boats, buses) that had taken me to work, on which I had written the same phrase were distributed in the bookshop of the Jeu de Paume. I aimed for the discovery of these postcards to be a surprise, and not on the wall as is customary, in the way that the headed sheets are exhibited.

MB: To investigate the structures of art sometimes you develop projects, books or curate exhibitions. In the case of the show "Objetos para un rato de inercia" (Objects for a moment of inertia), that took place in the Elba Benítez gallery in Madrid and which brought together works by David Askevold, Alighiero e Boetti, Luis Camnitzer, Barry Le Va and Francesc Torres. The declaration of principles was clear: "History, despite its insistence on the contrary, pertains to the present. History is always being made. It is a process not a result. History, and the writing of History, are one and the same thing." Is it a way of activating propositions that took place in the past, of which only the record or narrations are left? Do the historic investigations serve to understand the present better?

MGT: Definitely. If it wasn´t for the fact that I believe that each historic narrative, that I use as an excuse to generate another narrative, didn´t have an impact on our contemporaneity their wouldn´t be any reason to use them. In this sense, my initiatives are a conversation between my personal interests, with the understanding that I do them through a subjectivity that is situated in the present, as well as an interest in the more complex range of art that makes it possible for my work to exist. In this sense, it’s not just me as a person that activates these narratives, but a more complex system that supports the need for this revision.

MB: Your works function perfectly as stories, you meticulously investigate events, details about other artists’ projects, rumours and from there elaborate a history, a story in which the objective data and your interpretation coexist, sometimes endowed with a certain poetics. What is your stance in relation to more recent art history, to what is told, what is omitted and what is very superficially explained?

MGT: My pieces are very personal narratives that have to do with sharing my own experiences, desire or interest in a specific history. In this sense I see it as a way of making history, though very different from the one that pretends to tell the truth. Perhaps my narratives function as complements to those more official ones, as it is these details that are omitted that, most of the time, catch my attention.

MB: What is your working methodology?

MGT: When a piece is exhibited, a long time has passed from the moment when the episode in question excited me. The majority of times I begin an investigation, not very methodologically, about something that interests me and afterwards, at some point, I see the potential for it to convert into something that would be interesting to recount more publicly. The majority of times I rely on these things that have drawn my attention, the notes in a box on my desk and, little by little, different invitations end up also defining which ones are made and presented in specific temporal or geographic situations.

MB: What are the main points of confluence and also differences between your role as an artist and when you expand it on occasion to become curator of exhibitions?

MGT: To me there don’t seem to be that many differences. I am an artist, and my interventions as a curator have to do with looking for a different way of sharing my interests. Sometimes it can seem more to the point to make an exhibition that tells the story in a more personal manner, hence the exhibitions. But in reality I see it all as a single body of work.

MB: You often cite works or parts of work that are already made to begin your own process. Would you allow your works also to become the object of citations, appropriations, re-enactments or revisions?

MGT: It would be an honour if somebody one day saw them this way, and would continue these narratives, in whatever manner, to know that in some place in the world someone might continue to be interested. In the end, one works just for this to find people who have similar interests. I think that in the end my work comes down to this.

MB: Are you concerned about the notion of truth? Do you think that truth is possible in art?

MGT: No, I have absolutely no interest.

MB: What is your relation with the Internet, for you, is it a tool for research, communication or dissemination?

MGT: Obviously it is always my first point of contact with a subject and many times it leads me to investigate things in a less methodological way, a richer way. It situates normal people, everyday people, at the same level as books and official sources. Internet is present all the time, and I don´t blame it for often being wrong. I like it. What better way to divert an investigation towards something contradictory or further from the truth. It is there that one finds relations that potentially become something interesting, in the weaving of a new way of telling a story.

MB: Many of the works that you make at present could be disseminated perfectly via the Internet however they tend to be shown within the parameters of the institution. Have you ever thought about sometimes using the possibility of other routes to show and distribute your work?

MGT: I’ve never thought about it in depth. I believe that in the end I’m interested in the experiential part of art however contradictory that might seem. The use of films and slides, for example, has to do with having a cinematic experience, which would be lost if it was seen on a small monitor. I believe that there are pieces that can be disseminated on the Internet, but not the majority of mine. I am as concerned about the experience, as about the data within them.

MB: Do you think that the institutional framework (museums, art centres and also big events like Documenta or international biennales) is flexible and does it adapt to the new needs required by artistic practices?

MGT: Yes, it doesn’t trouble me. I believe that I have constantly tried to use this framework to talk about what I want to. Obviously there are limitations, but there is also a lot of flexibility. I believe that up until now, each time they have invited me to exhibit in a biennale or an exhibition of this type, I have ended up doing my work elsewhere. For me the work exists where it is executed and not where it is exhibited. That’s the least of it.

From A-Desk.

5/11/12

Lines of flight: urban resistance, dreamscapes and social play; Lorena Muñoz-Alonso, 2012

Some theoretical notes concerning the exhibition Desire Lines

Exactly one hundred years ago, in one of his most memorable poems,

Antonio Machado exhorted us to become more conscious of our choices, to

assume what is perhaps the most transcendental responsibility of our

existence as individuals: forging our own path in life rather than being

swept along by social pressure, fear or the paralysing shadow of

apathy. In that poem, the path is a metaphor for life, a powerful image

no less apt for being somewhat hackneyed. It is the perfect allegory for

an existential journey, with all of its inherent forks, choices and

decisions.

‘Desire lines’ is the name given to the alternative trails that emerge in a landscape— chosen itineraries eroded by wayfarers’ footprints, initially in an improvised manner that follows a transgressive urge, until they are consolidated and widened as a result of the kind of subversion that surpasses the individual to become collective. No path is ever made by one individual: it requires a group. It takes the repeated footsteps of many people to create these indelible marks.

This metaphor, which evokes both real and imaginary paths, is the

starting point for the exhibition, which features the work of eleven

international artists who explore subversive ways of navigating, using

and living the city. The eleven works selected for Desire Lines

take the urban fabric to be a complex, contradictory realm, brimming

with possibilities. A broad stage with the capacity to both repress our

deepest, destabilising desires and act as a catalyst for atavistic

spirits of resistance that can trigger collective action. In this

scenario the figure of the artist is key, as the embodiment of the

metropolitan denizen. The artist is the city dweller par excellence,

often roaming like a nomad from one metropolis to another, leading a

type of existence that normally verges on the precarious—one of the many

results of the gentrification process that the urban theorist and

economist Richard Florida has been studying since the beginning of the

21st century2—and therefore being a privileged witness to the joys and miseries of life in the big city.

If the artist exemplifies the citizen, he is thus the hero of the urban odyssey that billions of us face every day. The influential essay The Practice of Everyday Life3 (1984) by the theorist and scholar Michel de Certeau is dedicated to the “ordinary man. To a common hero, an ubiquitous character, walking in countless thousands on the streets. […] This anonymous hero is very ancient. He is the murmuring voice of societies. […] We witness the advent of the number. It comes along with democracy, the large city, administrations, cybernetics. It is a flexible and continuous mass, woven tight like a fabric with no rips nor darned patches, a multitude of quantified heroes who lose names and faces as they become the ciphered river of the streets, a mobile language of computations and rationalities that belong to no one.” It is hard to think of a more eloquent and poignant way to express the loss of identity and agency that the individual endures within an oppressive urban context. The artists and works featured in this show attempt to incite resistance to this situation, to remind us that we can choose our own path; that sometimes empowerment is found in the most inconsequential and impromptu decisions and actions.

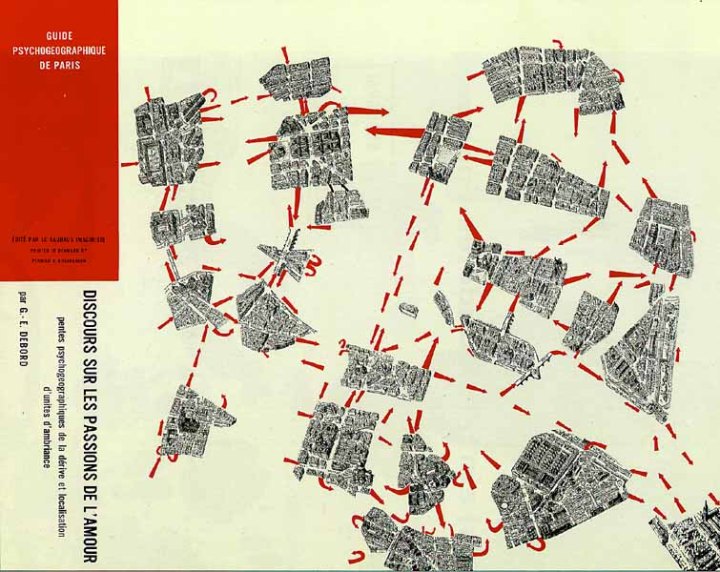

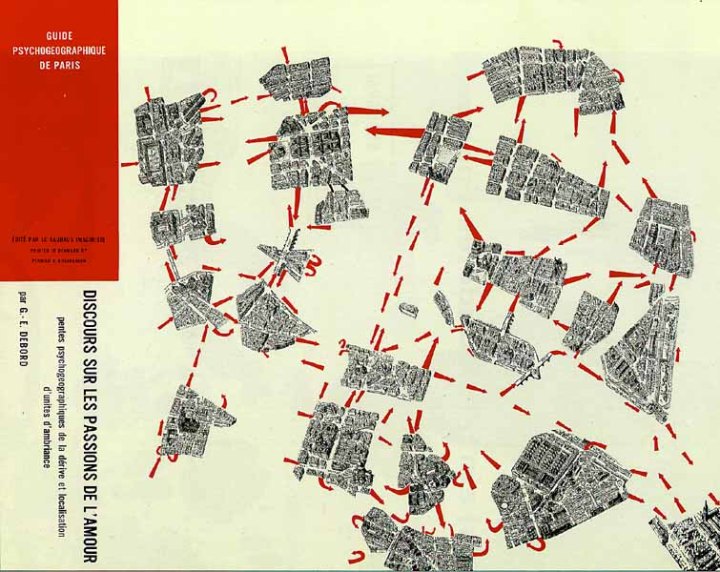

De Certeau described these activities, imbued with a tremendous subversive potential, as ‘tactics’, as opposed to ‘strategies’ –the institutional processes that establish the rules and conventions that govern societies. Tactics are the creative opportunities that operate between the gaps and slips of conventional thought and the patterns of everyday life. Of the contemporary philosophers who have promoted this type of liberating, playful, non-conformist behaviour, one of the most instrumental was undoubtedly Guy Debord, leader and founding member of the Situationist International (IS). This revolutionary group, created in 1957, reached its peak of influence with the publication of Society of the Spectacle (1967)4 and the subsequent May ’68 protests in Paris, a movement that borrowed both its ideas and most enduring slogans (such as the famous “Ne travaillez jamais!”). The group’s philosophy was based on the construction of ‘situations’ or environments in which one or more individuals were stimulated to critically analyse their everyday lives so they could identify and pursue their true desires. These ideas, developed by the artist Constant Nieuwenhuys alongside Debord, eventually crystallised into a fully fledged plan of action. Constant dedicated years to this project, entitled New Babylon, where he applied the concepts of what he called ‘unitary urbanism’. Because the Situationist critique of 20th-century urbanism questioned above all the degree of citizen participation, this “new Babylon” proposed a new form of urban planning based mostly on the concepts of mobility and play. Rather than a conventional urban development plan, this model fostered critical activities designed to promote participation in the city through a ‘mobile space of play’ and the construction of ‘situations’.

The idea of play, of understanding the city as a space in which to

act out our most pressing desires, is central to this philosophy and is

put into practice through the exercise of ‘drifting’ (dérive):

One of the basic Situationist practices is the ‘dérive’, a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances. ‘Dérives’ involve playful, constructive behaviour and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a ‘dérive’ one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. 5

The notion of drifting as productive or constructive play is particularly relevant in the context of this exhibition: play in the sense in which Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga explored it in his controversial essay Homo Ludens6, written in 1938, a time of utter political and social turmoil when the idea of play seemed, at best, a far-fetched irony and, at worst, an inappropriate and rather sick joke. According to Huizinga, the notion of play is inherent to the human condition and even predates it, as evidenced by the fact that it is found in the vast majority of animal species. Huizinga argued that the intrinsic value of play, besides being essential to the generation of culture, is that it permeates archetypal activities of human society such as language, myths and rituals. Rejecting the notion of play as something that is “not serious”, Huizinga explained that play creates a transitory order (or a set of rules), a community of players and a feeling of tension or instability, thus generating collective situations and social exchanges that constitute the first step towards the creation of ‘cultures’.

For example, Looking Up (2001) by Francis Alÿs, a work present

in this exhibition, is a video documentation of an action in which the

artist walks into the middle of Mexico City’s busy Plaza del Zócalo and,

standing impassively on the same spot, starts looking up at the sky. A

group of passers-by, surprised and curious, gradually gather behind the

artist, trying to see for themselves the elusive sight he is so keenly

observing. Looking Up is, in many ways, a practical joke turned

into an artwork, but it is a joke that unveils some distinctive human

traits: for instance, the fact that groups tend to follow a leader like a

herd of animals, often without the slightest guarantee of a worthwhile

outcome. More positively, Looking Up examines curiosity and play as agents that mobilise groups, reassuring us of our capacity to respond to events collectively.

The need to overcome that passive ‘herd’ mentality was also staunchly advocated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their seminal philosophical treatise Anti-Oedipus7 (1972), which denounced and challenged the human urge to repress oneself by means of ‘territories’ such as work, family, political parties or education: in short, any social construct born out of the exercise of power relations. To combat this drive and achieve what they called ‘deterritorialisation’, thereby triggering a chain reaction leading to change, it is necessary to forge ‘lines of flight’: brand-new paths in which one can break away from the material of the past.

That such ‘lines of flight’ seem to recall the concept of desire lines is no mere coincidence. For Deleuze and Guattari, desire (never in its strictly sexual sense) is the real force that can mobilise our freer and inevitably more transgressive impulses. This is why the aforementioned ‘territories’, from the workplace to the city, are such excellent machines for repressing our desires, making us docile and obedient as a result of the eternal battle between the social machines and us, the desiring-machines. As Deleuze and Guattari argue so eloquently throughout Anti-Oedipus, desire is socially repressed because any sign of uncontrolled behaviour has the capacity to destabilise the prescribed symbolic order. The lines that stem from desire can sabotage hegemony.

Desire lines—the real and imaginary ones—are an unmistakable symptom of the transgressive capacity of an individual desire that becomes a collective impulse. They symbolise the small acts of urban resistance that emerge from a strong impulse to deviate from the paths created and imposed by others. Regardless of the form these disruptions might take within the symbolic order—games, poetic acts, jokes, minor sabotages or a revolutionary and violent explosion—such transgressions can and should be extrapolated onto the field of human existential behaviour. They should be valued for what they are worth and used as tools for reviving the sensation, buried beneath layers of bureaucracy and social norms, that every life, every fate, is unique and worth fighting for, from the smallest routine struggle to the most pyrrhic battle. When disobedience leaves such a tangible mark, one must acknowledge it and take notice, rather than turning a blind eye, as evidenced by the protests that have shaken the world over these last two years, 2011 and 2012, from the 15 May Movement to the worldwide demonstrations of Occupy.

The works featured in Desire Lines represent different spirits of insurgence as well as tactics for appropriating and celebrating the city’s latent creative potential. We are honoured that artists as inspiring as Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Mark Aerial Waller, Francis Alÿs, Francisca Benítez, Mircea Cantor, Filipa César, Cyprien Gaillard, Regina de Miguel, Laura Oldfield Ford, Alejandra Salinas and Aeron Bergman, and John Smith have accepted our invitation to participate in this project and allowed us to exhibit their stimulating works, lending consistency to a set of enthusiastic ideas. It’s the turn of the audience now. We hope this journey is as enriching for them as it has been for the two curators.

-

This essay is part of the catalogue of the exhibition Desire Lines, curated by Lorena Muñoz-Alonso & Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz.

The exhibition will open on the 21st of November 2012 at the Espai Cultural Caja Madrid in Barcelona and will run until the 13t of January 2012.

Catalogue design by David G. Uzquiza.

-

Bibliography

1. This poem belongs to the anthology Campos de Castilla which Antonio Machado first published in 1912. Campos de Castilla, Madrid,Cátedra, 1992. Translation by the author of the essay.

2. Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, New York, Basic Books, 2002.

3. Michel de Certeau, L’invention du quotidien, tome 1: Arts de faire, Paris, Gallimard, 1990. (Published in English as The Practice of Everyday Life.)

4. Guy Debord, La sociéte du spectacle, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 1967. (Published in English as The Society of the Spectacle.)

5. Théorie de la dérive was originally published in Internationale Situationniste no. 2 (Paris, December 1958). A slightly different version had appeared in 1956 in the Belgian Surrealist magazine Les Lèvres Nues no. 9. (Published in English as “Theory of the Dérive”.)

6. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens, Boston, Beacon Press, 1955.

7. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Capitalisme et schizophrénie. L’anti-Œdipe, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1972. (Published in English as Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.)

Wayfarer, your footprints

are the way, and nothing else;

wayfarer, there is no path,

you make the path by walking.1

are the way, and nothing else;

wayfarer, there is no path,

you make the path by walking.1

Antonio Machado, Campos de Castilla, 1912

‘Desire lines’ is the name given to the alternative trails that emerge in a landscape— chosen itineraries eroded by wayfarers’ footprints, initially in an improvised manner that follows a transgressive urge, until they are consolidated and widened as a result of the kind of subversion that surpasses the individual to become collective. No path is ever made by one individual: it requires a group. It takes the repeated footsteps of many people to create these indelible marks.

Image of a desire line

If the artist exemplifies the citizen, he is thus the hero of the urban odyssey that billions of us face every day. The influential essay The Practice of Everyday Life3 (1984) by the theorist and scholar Michel de Certeau is dedicated to the “ordinary man. To a common hero, an ubiquitous character, walking in countless thousands on the streets. […] This anonymous hero is very ancient. He is the murmuring voice of societies. […] We witness the advent of the number. It comes along with democracy, the large city, administrations, cybernetics. It is a flexible and continuous mass, woven tight like a fabric with no rips nor darned patches, a multitude of quantified heroes who lose names and faces as they become the ciphered river of the streets, a mobile language of computations and rationalities that belong to no one.” It is hard to think of a more eloquent and poignant way to express the loss of identity and agency that the individual endures within an oppressive urban context. The artists and works featured in this show attempt to incite resistance to this situation, to remind us that we can choose our own path; that sometimes empowerment is found in the most inconsequential and impromptu decisions and actions.

De Certeau described these activities, imbued with a tremendous subversive potential, as ‘tactics’, as opposed to ‘strategies’ –the institutional processes that establish the rules and conventions that govern societies. Tactics are the creative opportunities that operate between the gaps and slips of conventional thought and the patterns of everyday life. Of the contemporary philosophers who have promoted this type of liberating, playful, non-conformist behaviour, one of the most instrumental was undoubtedly Guy Debord, leader and founding member of the Situationist International (IS). This revolutionary group, created in 1957, reached its peak of influence with the publication of Society of the Spectacle (1967)4 and the subsequent May ’68 protests in Paris, a movement that borrowed both its ideas and most enduring slogans (such as the famous “Ne travaillez jamais!”). The group’s philosophy was based on the construction of ‘situations’ or environments in which one or more individuals were stimulated to critically analyse their everyday lives so they could identify and pursue their true desires. These ideas, developed by the artist Constant Nieuwenhuys alongside Debord, eventually crystallised into a fully fledged plan of action. Constant dedicated years to this project, entitled New Babylon, where he applied the concepts of what he called ‘unitary urbanism’. Because the Situationist critique of 20th-century urbanism questioned above all the degree of citizen participation, this “new Babylon” proposed a new form of urban planning based mostly on the concepts of mobility and play. Rather than a conventional urban development plan, this model fostered critical activities designed to promote participation in the city through a ‘mobile space of play’ and the construction of ‘situations’.

Guy Debord, Guide Psychogeographique de Paris: Discours Sur Les Passions D’Amour, 1957

One of the basic Situationist practices is the ‘dérive’, a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances. ‘Dérives’ involve playful, constructive behaviour and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a ‘dérive’ one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. 5

Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive”

The notion of drifting as productive or constructive play is particularly relevant in the context of this exhibition: play in the sense in which Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga explored it in his controversial essay Homo Ludens6, written in 1938, a time of utter political and social turmoil when the idea of play seemed, at best, a far-fetched irony and, at worst, an inappropriate and rather sick joke. According to Huizinga, the notion of play is inherent to the human condition and even predates it, as evidenced by the fact that it is found in the vast majority of animal species. Huizinga argued that the intrinsic value of play, besides being essential to the generation of culture, is that it permeates archetypal activities of human society such as language, myths and rituals. Rejecting the notion of play as something that is “not serious”, Huizinga explained that play creates a transitory order (or a set of rules), a community of players and a feeling of tension or instability, thus generating collective situations and social exchanges that constitute the first step towards the creation of ‘cultures’.

Anna Halprin, City Dance, 1976-1977. Performance on the streets of San Francisco

The need to overcome that passive ‘herd’ mentality was also staunchly advocated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their seminal philosophical treatise Anti-Oedipus7 (1972), which denounced and challenged the human urge to repress oneself by means of ‘territories’ such as work, family, political parties or education: in short, any social construct born out of the exercise of power relations. To combat this drive and achieve what they called ‘deterritorialisation’, thereby triggering a chain reaction leading to change, it is necessary to forge ‘lines of flight’: brand-new paths in which one can break away from the material of the past.

That such ‘lines of flight’ seem to recall the concept of desire lines is no mere coincidence. For Deleuze and Guattari, desire (never in its strictly sexual sense) is the real force that can mobilise our freer and inevitably more transgressive impulses. This is why the aforementioned ‘territories’, from the workplace to the city, are such excellent machines for repressing our desires, making us docile and obedient as a result of the eternal battle between the social machines and us, the desiring-machines. As Deleuze and Guattari argue so eloquently throughout Anti-Oedipus, desire is socially repressed because any sign of uncontrolled behaviour has the capacity to destabilise the prescribed symbolic order. The lines that stem from desire can sabotage hegemony.

Desire lines—the real and imaginary ones—are an unmistakable symptom of the transgressive capacity of an individual desire that becomes a collective impulse. They symbolise the small acts of urban resistance that emerge from a strong impulse to deviate from the paths created and imposed by others. Regardless of the form these disruptions might take within the symbolic order—games, poetic acts, jokes, minor sabotages or a revolutionary and violent explosion—such transgressions can and should be extrapolated onto the field of human existential behaviour. They should be valued for what they are worth and used as tools for reviving the sensation, buried beneath layers of bureaucracy and social norms, that every life, every fate, is unique and worth fighting for, from the smallest routine struggle to the most pyrrhic battle. When disobedience leaves such a tangible mark, one must acknowledge it and take notice, rather than turning a blind eye, as evidenced by the protests that have shaken the world over these last two years, 2011 and 2012, from the 15 May Movement to the worldwide demonstrations of Occupy.

The works featured in Desire Lines represent different spirits of insurgence as well as tactics for appropriating and celebrating the city’s latent creative potential. We are honoured that artists as inspiring as Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Mark Aerial Waller, Francis Alÿs, Francisca Benítez, Mircea Cantor, Filipa César, Cyprien Gaillard, Regina de Miguel, Laura Oldfield Ford, Alejandra Salinas and Aeron Bergman, and John Smith have accepted our invitation to participate in this project and allowed us to exhibit their stimulating works, lending consistency to a set of enthusiastic ideas. It’s the turn of the audience now. We hope this journey is as enriching for them as it has been for the two curators.

-

This essay is part of the catalogue of the exhibition Desire Lines, curated by Lorena Muñoz-Alonso & Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz.

The exhibition will open on the 21st of November 2012 at the Espai Cultural Caja Madrid in Barcelona and will run until the 13t of January 2012.

Catalogue design by David G. Uzquiza.

-

Bibliography

1. This poem belongs to the anthology Campos de Castilla which Antonio Machado first published in 1912. Campos de Castilla, Madrid,Cátedra, 1992. Translation by the author of the essay.

2. Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, New York, Basic Books, 2002.

3. Michel de Certeau, L’invention du quotidien, tome 1: Arts de faire, Paris, Gallimard, 1990. (Published in English as The Practice of Everyday Life.)

4. Guy Debord, La sociéte du spectacle, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 1967. (Published in English as The Society of the Spectacle.)

5. Théorie de la dérive was originally published in Internationale Situationniste no. 2 (Paris, December 1958). A slightly different version had appeared in 1956 in the Belgian Surrealist magazine Les Lèvres Nues no. 9. (Published in English as “Theory of the Dérive”.)

6. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens, Boston, Beacon Press, 1955.

7. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Capitalisme et schizophrénie. L’anti-Œdipe, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1972. (Published in English as Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.)

Etiquetas:

Cartografía,

desire lines,

mapa,

mapa conceptual

Achilles Gildo Rizzoli (1896–1981), anonymous during his lifetime, has since his death become celebrated as an outsider artist. He is an unusual example of an "outsider" artist who had considerable formal training in drawing.

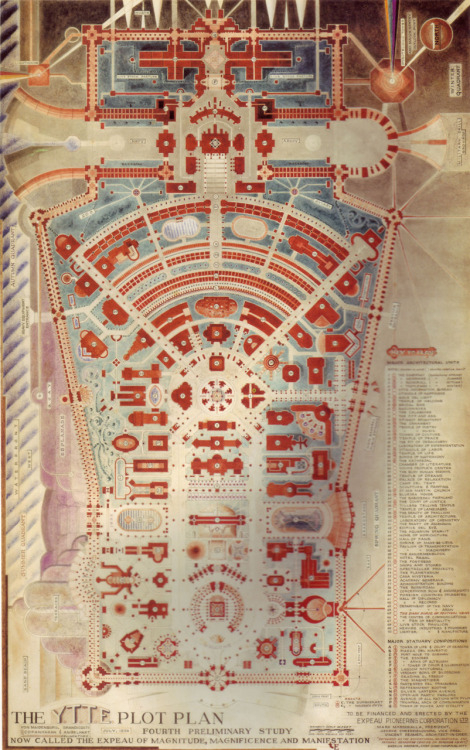

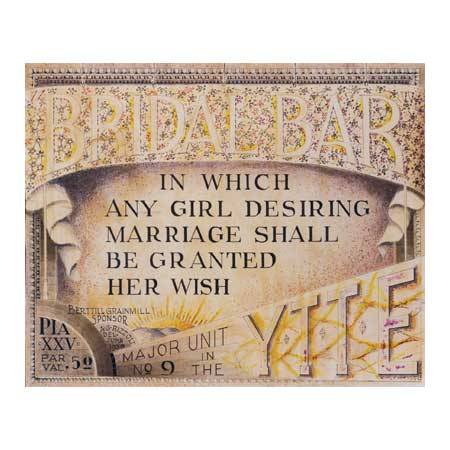

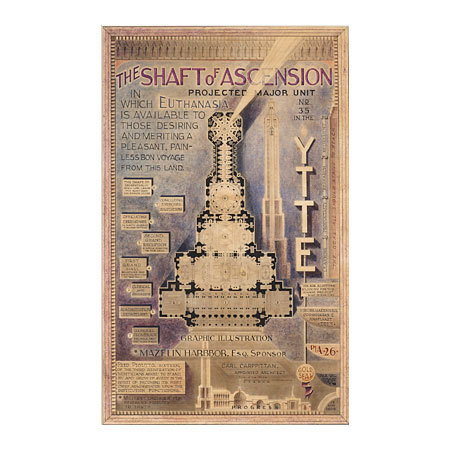

Born in Marin County, California, Rizzoli lived near the U.S. city of San Francisco, where he was employed as an architectural draftsman. After his death, a group of elaborate drawings came to light, many in the form of maps and architectural renderings that described an imaginary world exposition (much of which was designated "Y.T.T.E.," for "Yield To Total Elation"). The drawings include "portraits" of his mother (whom he lived with until her death in 1937) and neighborhood children "symbolically sketched" in the form of fanciful neo-baroque buildings.

Rizzoli published one novel, The Colonnade (1931), under the pseudonym Peter Metermaid.

A film was made about his life and work, called Yield to Total Elation: The Life and Art of Achilles Rizzoli.

From eaderdigest.

Etiquetas:

AG Rizolli,

Plan,

Visionary architecture,

YTTE

1/11/12

56 Broken Kindle Screens; Sebastian Schmieg and Silvio Lorusso, 2012

56 Broken Kindle Screens, 2012 is a collaboration project by Sebastian Schmieg and Silvio Lorusso_

"56 Broken Kindle Screens is a print on demand paperback that consists

of found photos depicting broken Kindle screens. The Kindle is Amazon's

e-reading device which is by default connected to the company's book

store.

19/9/12

Proponen un experimento para transferir información entre el pasado y el futuro

"El vacío, tal y como lo entendemos clásicamente, es un estado completamente desprovisto de materia, pero cuánticamente está lleno de partículas virtuales: Es lo que se conoce como fluctuaciones cuánticas del vacío", explica Borja Peropadre, investigador del Instituto de Física Fundamental (CSIC). Investigadores de este centro y de la Universidad de Waterloo (Canadá) proponen un experimento que permite la transferencia de información entre el pasado y el futuro usando este vacío cuántico. Los científicos han conseguido explotar sus propiedades utilizando la emergente tecnología de los circuitos superconductores, según un trabajo que publican en la revista Physical Review Letters.

"Gracias a esas fluctuaciones, es posible hacer que el vacío esté entrelazado en el tiempo; es decir, el vacío que hay ahora y el que habrá en un instante de tiempo posterior, presentan fuertes correlaciones cuánticas", aclara Peropadre. Por su parte, el director del estudio, Carlos Sabín, destaca el papel de los circuitos superconductores:"Permiten reproducir la interacción entre materia y radiación, pero con un grado de control asombroso. No sólo ayudan a controlar la intensidad de la interacción entre átomos y luz, sino también el tiempo que dura la misma. Gracias a ello, hemos podido amplificar efectos cuánticos que, de otra forma, serían imposibles de detectar".

Los científicos han entrelazado con fuerza átomos P del pasado con los F del futuro

De

este modo, haciendo interaccionar fuertemente dos átomos P (pasado) y F

(futuro) con el vacío de un campo cuántico en distintos instantes de

tiempo, los científicos han encontrado que P y F acaban fuertemente

entrelazados. "Es importante señalar que no sólo es que los átomos no

hayan interaccionado entre ellos, sino que en un mundo clásico, ni

siquiera sabrían de su existencia mutua", comentan los investigadores.

Futuras memorías cuánticas

Desde el punto de vista tecnológico, una aplicación "muy importante" -según los autores- de este resultado es el uso de esta transferencia de entrelazamiento para fabricar en el futuro memorias cuánticas, capaces de retener este tipo de información. "Codificando el estado de un átomo P en el vacío de un campo cuántico, podremos recuperarlo pasado un tiempo en el átomo F", señala Peropadre. "Y esa información de P, que está siendo ‘memorizada' por el vacío, será transferida después al átomo F sin pérdida de información. Todo ello gracias a la extracción de las correlaciones temporales del vacío".Contemporary Cartographies. Drawing Thought at CaixaForum, 2012.

Michael Druks. Druksland–Physical and Socia, 15 January 1974, 11.30 am., 1974.

© Michael Druks. Fotografía: England & Co Gallery, London

We map our world in order to gain a glimpse of the reality in which we live.

Since time immemorial, maps have been used to represent, translate and

encode all kinds of physical, mental and emotional territories. Our

representation of the world has evolved in recent centuries and, today, with

globalisation and the Internet, traditional concepts of time and space, along

with methods for representing the world and knowledge, have been

definitively transformed. In response to this paradigm shift, contemporary

artists question systems of representation and suggest new formulas for

classifying reality. The ultimate aim of Contemporary Cartographies.

Drawing Thought, an exhibition that seeks to draw a map formed by

cartographies created by twentieth- and twenty-first century artists, is to

invite the visitor to question both the systems of representation that we use

and the ideas that underpin them. The exhibition, organised and produced

by ”la Caixa” Foundation, is comprises more than 140 works in a wide

range of formats – from maps and drawings to video installations and

digital art – on loan from the collections of several major contemporary art

galleries. The artists represented include such essential figures as

Salvador Dalí, Paul Klee, Marcel Duchamp, Yves Klein, Gordon Matta-Clark,

Richard Hamilton, Mona Hatoum and Richard Long, shoulder-to-shoulder

with a roster of contemporary artists, including Art & Language, Artur

Barrio, Carolee Schneemann, Ana Mendieta, Erick Beltrán, On Kawara,

Alighiero Boetti, Thomas Hirschhorn and Francis Alÿs, amongst others.

Finally, the exhibition is completed by a series of revealing documents

drawn up by experts from other fields, such as Santiago Ramón y Cajal,

Lewis Carroll and Carl Gustav Jung.

Contemporary Cartographies. Drawing Thought. Organised and produced by:

”la Caixa” Foundation. Dates: 25 July - 28 October 2012. Place: CaixaForum

Barcelona (Av. de Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia, 6-8). Curator: Helena Tatay.

(...)

4

Physical, mental and emotional territories

Humans have always needed to design and build structures in order to

understand the chaos that is life. Maps break down reality into fragments,

enabling it to be presented in the shape of tables. In this way, we translate and

codify, not only physical space, but also knowledge, feelings, desires and life

experiences.

Representing the Earth on a plane, projecting a three-dimensional object in two

dimensions, was an astounding transformation. This process enables us to

grasp the idea of space, which has shaped European thinking. As the

geographer Franco Farinelli notes, since the beginning of European knowledge

there has been no other way of knowing things except through their image. It is

difficult for us to go beyond their appearance, their representation.

In the seventeenth century, classifications and phenomena began to be drawn

on a plane. Mapmaking knowledge was combined with statistical skills. In this

way, data maps emerged, helping to visualise knowledge and converting it into

science. A century later, linked to the colonial expansion of certain European

countries, scientific cartography came into being. At the same time, maps of

emotions began to appear in French salons hosted by women. Since then,

maps have been used to represent and make visible physical, mental and

emotional territories of all kinds.

In the twentieth century, technical advances such as the airplane and

photograph, which enabled reality to be reproduced exactly, wrought changes in

the way the world was represented. Moreover, non-material communication –

the telegraph and the telephone – caused the “crisis of space” that was so ably

reflected by the cubists.

Internet finally dispelled all traditional concepts of time and space. The

contemporary space is a heterogeneous space. We are aware that we live in a

network of relations and material and non-material flows, but we still do not

possess a model to represent this invisible network. We live in tension between

what we were and can think and these new things that we are unable to

represent.

This exhibition explores a theme that has unattainable ramifications. Based on

art (a microspace for freedom in which models of knowledge can be

reconsidered and redefined) it proposes a map – arbitrary, subjective and

incomplete, like all maps – of the cartographies formulated by twentieth-century

and contemporary artists. This map invites us to question the systems of

representation that we use, and the ideas that underlie them.

Artists:

Artistas:

Ignasi Aballí, Francis Alÿs, Efrén Álvarez, Giovanni Anselmo, Art & Language, Zbynék Baladrán, Artur Barrio, Lothar Baumgarthen, Erick Beltrán, Zarina Bhimji, Ursula Biemann, Cezary Bodzianowski, Alighiero Boettti, Christian Boltanski, Marcel Broodthaers, Stanley Brown, Trisha Brown, Bureau d'Études, Los Carpinteros, Constant, Raimond Chaves y Gilda Mantilla, Salvador Dalí, Guy Debord, Michael Drucks, Marcel Duchamp, El Lissitzky, Valie Export, Evru, Öyvind Fahlström, Félix González-Torres, Milan Grygar, Richard Hamilton, Zarina Hashmi, Mona Hatoum, David Hammons, Thomas Hirschhorn, Bas Jan Ader, On Kawara, Allan Kaprow, William Kentridge, Robert Kinmont, Paul Klee, Yves Klein, Hilma af Klint, Guillermo Kuitca, Emma Kunz, Mark Lombardi, Rogelio López Cuenca, Richard Long, Cristina Lucas, Anna Maria Maiolino, Kris Martin, Gordon Matta-Clark, Ana Mendieta, Norah Napaljarri Nelson, Dorothy Napangardi, Rivane Neuenschwander, Perejaume, Grayson Perry, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Vahida Ramujkic, Till Roeskens, Rotor, Ralph Rumney, Ed Ruscha, Carolee Schneemann, Robert Smithson, Saul Steinberg, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Willy Tjungurrayi, Joaquín Torres García, Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, Adriana Varejao, Oriol Vilapuig, Kara Walker, Adolf Wölfli.

More in the web of CaixaForum.

More info in the Pdf.

Very nice tumblr of the curator, Helena Tatay.

And i have to say that i´m more than happy to be in the links section.

Since time immemorial, maps have been used to represent, translate and

encode all kinds of physical, mental and emotional territories. Our

representation of the world has evolved in recent centuries and, today, with

globalisation and the Internet, traditional concepts of time and space, along

with methods for representing the world and knowledge, have been

definitively transformed. In response to this paradigm shift, contemporary

artists question systems of representation and suggest new formulas for

classifying reality. The ultimate aim of Contemporary Cartographies.

Drawing Thought, an exhibition that seeks to draw a map formed by

cartographies created by twentieth- and twenty-first century artists, is to

invite the visitor to question both the systems of representation that we use

and the ideas that underpin them. The exhibition, organised and produced

by ”la Caixa” Foundation, is comprises more than 140 works in a wide

range of formats – from maps and drawings to video installations and

digital art – on loan from the collections of several major contemporary art

galleries. The artists represented include such essential figures as

Salvador Dalí, Paul Klee, Marcel Duchamp, Yves Klein, Gordon Matta-Clark,

Richard Hamilton, Mona Hatoum and Richard Long, shoulder-to-shoulder

with a roster of contemporary artists, including Art & Language, Artur

Barrio, Carolee Schneemann, Ana Mendieta, Erick Beltrán, On Kawara,

Alighiero Boetti, Thomas Hirschhorn and Francis Alÿs, amongst others.

Finally, the exhibition is completed by a series of revealing documents

drawn up by experts from other fields, such as Santiago Ramón y Cajal,

Lewis Carroll and Carl Gustav Jung.

Contemporary Cartographies. Drawing Thought. Organised and produced by:

”la Caixa” Foundation. Dates: 25 July - 28 October 2012. Place: CaixaForum

Barcelona (Av. de Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia, 6-8). Curator: Helena Tatay.

(...)

4

Physical, mental and emotional territories

Humans have always needed to design and build structures in order to

understand the chaos that is life. Maps break down reality into fragments,

enabling it to be presented in the shape of tables. In this way, we translate and

codify, not only physical space, but also knowledge, feelings, desires and life

experiences.

Representing the Earth on a plane, projecting a three-dimensional object in two

dimensions, was an astounding transformation. This process enables us to

grasp the idea of space, which has shaped European thinking. As the

geographer Franco Farinelli notes, since the beginning of European knowledge

there has been no other way of knowing things except through their image. It is

difficult for us to go beyond their appearance, their representation.

In the seventeenth century, classifications and phenomena began to be drawn

on a plane. Mapmaking knowledge was combined with statistical skills. In this

way, data maps emerged, helping to visualise knowledge and converting it into

science. A century later, linked to the colonial expansion of certain European

countries, scientific cartography came into being. At the same time, maps of

emotions began to appear in French salons hosted by women. Since then,

maps have been used to represent and make visible physical, mental and

emotional territories of all kinds.

In the twentieth century, technical advances such as the airplane and

photograph, which enabled reality to be reproduced exactly, wrought changes in

the way the world was represented. Moreover, non-material communication –

the telegraph and the telephone – caused the “crisis of space” that was so ably

reflected by the cubists.

Internet finally dispelled all traditional concepts of time and space. The

contemporary space is a heterogeneous space. We are aware that we live in a

network of relations and material and non-material flows, but we still do not

possess a model to represent this invisible network. We live in tension between

what we were and can think and these new things that we are unable to

represent.

This exhibition explores a theme that has unattainable ramifications. Based on

art (a microspace for freedom in which models of knowledge can be

reconsidered and redefined) it proposes a map – arbitrary, subjective and

incomplete, like all maps – of the cartographies formulated by twentieth-century

and contemporary artists. This map invites us to question the systems of

representation that we use, and the ideas that underlie them.

Artists:

Artistas:

Ignasi Aballí, Francis Alÿs, Efrén Álvarez, Giovanni Anselmo, Art & Language, Zbynék Baladrán, Artur Barrio, Lothar Baumgarthen, Erick Beltrán, Zarina Bhimji, Ursula Biemann, Cezary Bodzianowski, Alighiero Boettti, Christian Boltanski, Marcel Broodthaers, Stanley Brown, Trisha Brown, Bureau d'Études, Los Carpinteros, Constant, Raimond Chaves y Gilda Mantilla, Salvador Dalí, Guy Debord, Michael Drucks, Marcel Duchamp, El Lissitzky, Valie Export, Evru, Öyvind Fahlström, Félix González-Torres, Milan Grygar, Richard Hamilton, Zarina Hashmi, Mona Hatoum, David Hammons, Thomas Hirschhorn, Bas Jan Ader, On Kawara, Allan Kaprow, William Kentridge, Robert Kinmont, Paul Klee, Yves Klein, Hilma af Klint, Guillermo Kuitca, Emma Kunz, Mark Lombardi, Rogelio López Cuenca, Richard Long, Cristina Lucas, Anna Maria Maiolino, Kris Martin, Gordon Matta-Clark, Ana Mendieta, Norah Napaljarri Nelson, Dorothy Napangardi, Rivane Neuenschwander, Perejaume, Grayson Perry, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Vahida Ramujkic, Till Roeskens, Rotor, Ralph Rumney, Ed Ruscha, Carolee Schneemann, Robert Smithson, Saul Steinberg, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Willy Tjungurrayi, Joaquín Torres García, Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, Adriana Varejao, Oriol Vilapuig, Kara Walker, Adolf Wölfli.

More in the web of CaixaForum.

More info in the Pdf.

Very nice tumblr of the curator, Helena Tatay.

And i have to say that i´m more than happy to be in the links section.

TEATRO GEOGRAFICO ANTIGUO Y MODERNO DEL REYNO DE SICILIA, 1686

Se

trata de un extraordinario atlas militar, en el que destaca

particularmente la cantidad, calidad y naturaleza de sus ilustraciones.

Aunque

en sus páginas encontramos representaciones de fortalezas y un especial

protagonismo de las murallas y los sistemas defensivos en sus vistas de

ciudades, el Teatro Geográfico destaca por la pluralidad de

ilustraciones que contiene, que son mucho más heterogéneas que las de un

mero atlas militar. Encontramos representados desde los principales

monumentos civiles y religiosos de Palermo y Mesina, a escenas

mitológicas ligadas a la isla o representaciones de actos

institucionales de la corte virreinal.

9/9/12

Project ‘Ground Truth’ - How Google Builds It’s Maps

Fascinating article on the workings on Google Maps and how it relates

to the bigger picture of personal information technology - via The Atlantic:

Founded here.

Behind every Google Map, there is a much more complex map that’s the key to your queries but hidden from your view. The deep map contains the logic of places: their no-left-turns and freeway on-ramps, speed limits and traffic conditions. This is the data that you’re drawing from when you ask Google to navigate you from point A to point B — and last week, Google showed me the internal map and demonstrated how it was built. It’s the first time the company has let anyone watch how the project it calls GT, or “Ground Truth,” actually works.More Here

The company opened up at a key moment in its evolution. The company began as an online search company that made money almost exclusively from selling ads based on what you were querying for. But then the mobile world exploded. Where you’re searching has become almost important as what you’re searching. Google responded by creating an operating system, brand, and ecosystem in Android that has become the only significant rival to Apple’s iOS.

And for good reason. If Google’s mission is to organize all the world’s information, the most important challenge — far larger than indexing the web — is to take the world’s physical information and make it accessible and useful.

“If you look at the offline world, the real world in which we live, that information is not entirely online,” Manik Gupta, the senior product manager for Google Maps, told me. “Increasingly as we go about our lives, we are trying to bridge that gap between what we see in the real world and [the online world], and Maps really plays that part.”

Founded here.

7/8/12

Clement Valla; The Universal Texture, 2012

Clement Valla

Work from The Universal Texture (including the full post / essay from Rhizome)

These artists (…) counter the database, understood as a structure of dehumanized power, with the collection, as a form of idiosyncratic, unsystematic, and human memory. They collect what interests them, whatever they feel can and should be included in a meaning system. They describe, critique, and finally challenge the dynamics of the database, forcing it to evolve.1I collect Google Earth images. I discovered them by accident, these particularly strange snapshots, where the illusion of a seamless and accurate representation of the Earth’s surface seems to break down. I was Google Earth-ing, when I noticed that a striking number of buildings looked like they were upside down. I could tell there were two competing visual inputs here —the 3D model that formed the surface of the earth, and the mapping of the aerial photography; they didn’t match up. Depth cues in the aerial photographs, like shadows and lighting, were not aligning with the depth cues of the 3D model.

The competing visual inputs I had noticed produced some exceptional imagery, and I began to find more and start a collection. At first, I thought they were glitches, or errors in the algorithm, but looking closer, I realized the situation was actually more interesting — these images are not glitches. They are the absolute logical result of the system. They are an edge condition—an anomaly within the system, a nonstandard, an outlier, even, but not an error. These jarring moments expose how Google Earth works, focusing our attention on the software. They are seams which reveal a new model of seeing and of representing our world – as dynamic, ever-changing data from a myriad of different sources – endlessly combined, constantly updated, creating a seamless illusion.

3D Images like those in Google Earth are generated through a process called texture mapping. Texture mapping is a technology developed by Ed Catmull in the 1970′s. In 3D modeling, a texture map is a flat image that gets applied to the surface of a 3D model, like a label on a can or a bottle of soda. Textures typically represent a flat expanse with very little depth of field, meant to mimic surface properties of an object. Textures are more like a scan than a photograph. The surface represented in a texture coincides with the surface of the picture plane, unlike a photograph that represents a space beyond the picture plane. This difference might be summed up another way: we see through a photograph, we look at a texture. This is an important distinction in 3D modeling, because textures are stretched across the surface of a 3D model, in essence becoming the skin for the model.

Google Earth’s textures however, are not shallow or flat. They are photographs that we look through into a space represented beyond—a space our brain interprets as having three dimensions and depth. We see space in the aerial photographs because of light and shadows and because of our prior knowledge of experienced space. When these photographs get distorted and stretched across the 3D topography of the earth, we are both looking at the distorted picture plane, and through the same picture plane at the space depicted in the texture. In other words, we are looking at two spaces simultaneously. Most of the time this doubling of spaces in Google Earth goes unnoticed, but sometimes the two spaces are so different, that things look strange, vertiginous, or plain wrong. But they’re not wrong. They reveal Google’s system used to map the earth — The Universal Texture.

The Universal Texture is a Google patent for mapping textures onto a 3D model of the entire globe.2 At its core the Universal Texture is just an optimal way to generate a texture map of the earth. As its name implies, the Universal Texture promises a god-like (or drone-like) uninterrupted navigation of our planet — not a tiled series of discrete maps, but a flowing and fluid experience. This experience is so different, so much more seamless than previous technologies, that it is an achievement quite like what the escalator did to shopping:

No invention has had the importance for and impact on shopping as the escalator. As opposed to the elevator, which is limited in terms of the numbers it can transport between different floors and which through its very mechanism insists on division, the escalator accommodates and combines any flow, efficiently creates fluid transitions between one level and another, and even blurs the distinction between separate levels and individual spaces.3In the digital media world, this fluid continuity is analogous to the infinite scroll’s effect on Tumblr. In Google Earth, the Universal Texture delivers a smooth, complete and easily accessible knowledge of the planet’s surface. The Universal Texture is able to take a giant photo collage made up of aerial photographs from all kinds of different sources — various companies, governments, mapping institutes — and map it onto a three-dimensional model assembled from as many distinct sources. It blends these disparate data together into a seamless space – like the escalator merges floors in a shopping mall.

Our mechanical processes for creating images have habituated us into thinking in terms of snapshots – discrete segments of time and space (no matter how close together those discrete segments get, we still count in frames per second and image aspect ratios). But Google is thinking in continuity. The images produced by Google Earth are quite unlike a photograph that bears an indexical relationship to a given space at a given time. Rather, they are hybrid images, a patchwork of two-dimensional photographic data and three-dimensional topographic data extracted from a slew of sources, data-mined, pre-processed, blended and merged in real-time. Google Earth is essentially a database disguised as a photographic representation.