Wayfarer, your footprints

are the way, and nothing else;

wayfarer, there is no path,

you make the path by walking.1

are the way, and nothing else;

wayfarer, there is no path,

you make the path by walking.1

Antonio Machado, Campos de Castilla, 1912

‘Desire lines’ is the name given to the alternative trails that emerge in a landscape— chosen itineraries eroded by wayfarers’ footprints, initially in an improvised manner that follows a transgressive urge, until they are consolidated and widened as a result of the kind of subversion that surpasses the individual to become collective. No path is ever made by one individual: it requires a group. It takes the repeated footsteps of many people to create these indelible marks.

Image of a desire line

If the artist exemplifies the citizen, he is thus the hero of the urban odyssey that billions of us face every day. The influential essay The Practice of Everyday Life3 (1984) by the theorist and scholar Michel de Certeau is dedicated to the “ordinary man. To a common hero, an ubiquitous character, walking in countless thousands on the streets. […] This anonymous hero is very ancient. He is the murmuring voice of societies. […] We witness the advent of the number. It comes along with democracy, the large city, administrations, cybernetics. It is a flexible and continuous mass, woven tight like a fabric with no rips nor darned patches, a multitude of quantified heroes who lose names and faces as they become the ciphered river of the streets, a mobile language of computations and rationalities that belong to no one.” It is hard to think of a more eloquent and poignant way to express the loss of identity and agency that the individual endures within an oppressive urban context. The artists and works featured in this show attempt to incite resistance to this situation, to remind us that we can choose our own path; that sometimes empowerment is found in the most inconsequential and impromptu decisions and actions.

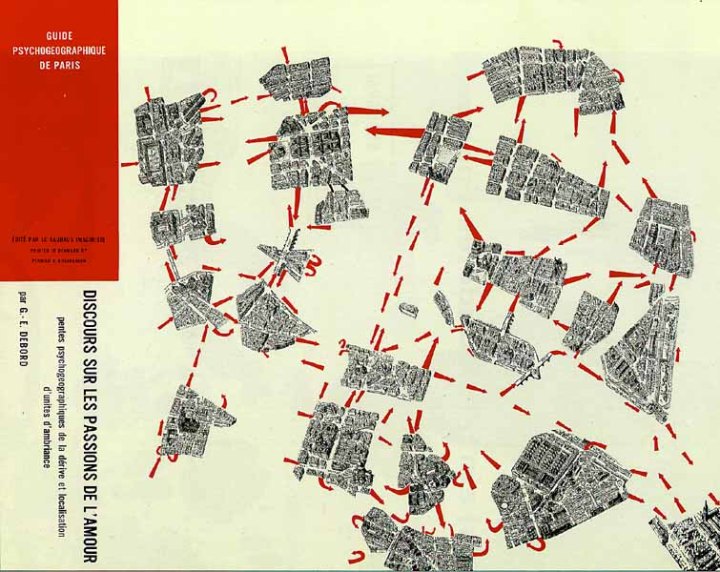

De Certeau described these activities, imbued with a tremendous subversive potential, as ‘tactics’, as opposed to ‘strategies’ –the institutional processes that establish the rules and conventions that govern societies. Tactics are the creative opportunities that operate between the gaps and slips of conventional thought and the patterns of everyday life. Of the contemporary philosophers who have promoted this type of liberating, playful, non-conformist behaviour, one of the most instrumental was undoubtedly Guy Debord, leader and founding member of the Situationist International (IS). This revolutionary group, created in 1957, reached its peak of influence with the publication of Society of the Spectacle (1967)4 and the subsequent May ’68 protests in Paris, a movement that borrowed both its ideas and most enduring slogans (such as the famous “Ne travaillez jamais!”). The group’s philosophy was based on the construction of ‘situations’ or environments in which one or more individuals were stimulated to critically analyse their everyday lives so they could identify and pursue their true desires. These ideas, developed by the artist Constant Nieuwenhuys alongside Debord, eventually crystallised into a fully fledged plan of action. Constant dedicated years to this project, entitled New Babylon, where he applied the concepts of what he called ‘unitary urbanism’. Because the Situationist critique of 20th-century urbanism questioned above all the degree of citizen participation, this “new Babylon” proposed a new form of urban planning based mostly on the concepts of mobility and play. Rather than a conventional urban development plan, this model fostered critical activities designed to promote participation in the city through a ‘mobile space of play’ and the construction of ‘situations’.

Guy Debord, Guide Psychogeographique de Paris: Discours Sur Les Passions D’Amour, 1957

One of the basic Situationist practices is the ‘dérive’, a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances. ‘Dérives’ involve playful, constructive behaviour and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll. In a ‘dérive’ one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. 5

Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive”

The notion of drifting as productive or constructive play is particularly relevant in the context of this exhibition: play in the sense in which Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga explored it in his controversial essay Homo Ludens6, written in 1938, a time of utter political and social turmoil when the idea of play seemed, at best, a far-fetched irony and, at worst, an inappropriate and rather sick joke. According to Huizinga, the notion of play is inherent to the human condition and even predates it, as evidenced by the fact that it is found in the vast majority of animal species. Huizinga argued that the intrinsic value of play, besides being essential to the generation of culture, is that it permeates archetypal activities of human society such as language, myths and rituals. Rejecting the notion of play as something that is “not serious”, Huizinga explained that play creates a transitory order (or a set of rules), a community of players and a feeling of tension or instability, thus generating collective situations and social exchanges that constitute the first step towards the creation of ‘cultures’.

Anna Halprin, City Dance, 1976-1977. Performance on the streets of San Francisco

The need to overcome that passive ‘herd’ mentality was also staunchly advocated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their seminal philosophical treatise Anti-Oedipus7 (1972), which denounced and challenged the human urge to repress oneself by means of ‘territories’ such as work, family, political parties or education: in short, any social construct born out of the exercise of power relations. To combat this drive and achieve what they called ‘deterritorialisation’, thereby triggering a chain reaction leading to change, it is necessary to forge ‘lines of flight’: brand-new paths in which one can break away from the material of the past.

That such ‘lines of flight’ seem to recall the concept of desire lines is no mere coincidence. For Deleuze and Guattari, desire (never in its strictly sexual sense) is the real force that can mobilise our freer and inevitably more transgressive impulses. This is why the aforementioned ‘territories’, from the workplace to the city, are such excellent machines for repressing our desires, making us docile and obedient as a result of the eternal battle between the social machines and us, the desiring-machines. As Deleuze and Guattari argue so eloquently throughout Anti-Oedipus, desire is socially repressed because any sign of uncontrolled behaviour has the capacity to destabilise the prescribed symbolic order. The lines that stem from desire can sabotage hegemony.

Desire lines—the real and imaginary ones—are an unmistakable symptom of the transgressive capacity of an individual desire that becomes a collective impulse. They symbolise the small acts of urban resistance that emerge from a strong impulse to deviate from the paths created and imposed by others. Regardless of the form these disruptions might take within the symbolic order—games, poetic acts, jokes, minor sabotages or a revolutionary and violent explosion—such transgressions can and should be extrapolated onto the field of human existential behaviour. They should be valued for what they are worth and used as tools for reviving the sensation, buried beneath layers of bureaucracy and social norms, that every life, every fate, is unique and worth fighting for, from the smallest routine struggle to the most pyrrhic battle. When disobedience leaves such a tangible mark, one must acknowledge it and take notice, rather than turning a blind eye, as evidenced by the protests that have shaken the world over these last two years, 2011 and 2012, from the 15 May Movement to the worldwide demonstrations of Occupy.

The works featured in Desire Lines represent different spirits of insurgence as well as tactics for appropriating and celebrating the city’s latent creative potential. We are honoured that artists as inspiring as Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Mark Aerial Waller, Francis Alÿs, Francisca Benítez, Mircea Cantor, Filipa César, Cyprien Gaillard, Regina de Miguel, Laura Oldfield Ford, Alejandra Salinas and Aeron Bergman, and John Smith have accepted our invitation to participate in this project and allowed us to exhibit their stimulating works, lending consistency to a set of enthusiastic ideas. It’s the turn of the audience now. We hope this journey is as enriching for them as it has been for the two curators.

-

This essay is part of the catalogue of the exhibition Desire Lines, curated by Lorena Muñoz-Alonso & Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz.

The exhibition will open on the 21st of November 2012 at the Espai Cultural Caja Madrid in Barcelona and will run until the 13t of January 2012.

Catalogue design by David G. Uzquiza.

-

Bibliography

1. This poem belongs to the anthology Campos de Castilla which Antonio Machado first published in 1912. Campos de Castilla, Madrid,Cátedra, 1992. Translation by the author of the essay.

2. Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, New York, Basic Books, 2002.

3. Michel de Certeau, L’invention du quotidien, tome 1: Arts de faire, Paris, Gallimard, 1990. (Published in English as The Practice of Everyday Life.)

4. Guy Debord, La sociéte du spectacle, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 1967. (Published in English as The Society of the Spectacle.)

5. Théorie de la dérive was originally published in Internationale Situationniste no. 2 (Paris, December 1958). A slightly different version had appeared in 1956 in the Belgian Surrealist magazine Les Lèvres Nues no. 9. (Published in English as “Theory of the Dérive”.)

6. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens, Boston, Beacon Press, 1955.

7. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Capitalisme et schizophrénie. L’anti-Œdipe, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1972. (Published in English as Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario