Last year, Triple Canopy published Alix Rule and David Levine’s “International Art English.”1

As a broad critique of globalized artspeak semantics, the essay has

since sparked many debates around the exaggerated claims and imprecise

promotional language of contemporary art. In this issue of e-flux journal, Martha Rosler and Hito Steyerl each respond to Rule and Levine’s essay.

***

Let’s start with something else. Ever heard of the English Disco

Lovers? A fantastic online project trying to outgun (or rather outlove)

their acronym twin—the racist English Defence League, also abbreviated

as “EDL”—on Facebook and Twitter. For this they use the bilingual slogan

“Unus Mundas, Una Gens, Unus Disco (One World, One Race, One Disco).”

The English Disco Lovers’ name is, of course, a deliberate misreading of

the original, a successfully failed copy coming into being via

translation.

Likewise in the case of many exhibition press releases—or so Alix

Rule and David Levine claim in their widely read essay “International

Art English.”2

International Art English, or “IAE,” is their name for the decisively

amateurish English language used in contemporary art press releases. In

order to investigate IAE, Rule and Levine undertake a statistical

inquiry into a set of such texts distributed by e-flux.3

They conclude that the texts are written in a skewed English full of

grandiose and empty jargon often carelessly ripped from mistranslations

of continental philosophy.

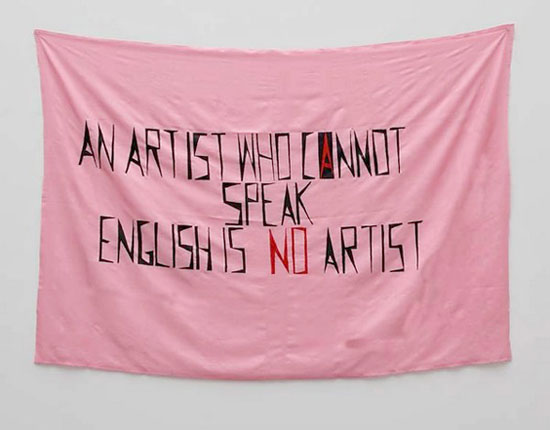

Mladen Stilinović, An Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is No Artist, 1992.

So far so good. But what are they actually looking at? In the

unstated hierarchies of publishing, press releases barely even make it

to the bottom. They have the lifespan of a fruit fly and the

farsightedness of a grocery list. Armies of these hastily aggregated,

briefly circulated, poorly phrased missives constantly vie for attention

in our clogged inboxes. Typically written by overworked and underpaid

assistants and interns across the world, the press release’s pompous

prose contrasts most acutely with the lowly status of its authors. Press

releases are the art world’s equivalent of digital spam, vehicles for

serial name-dropping and para-deconstructive waxing, in close

competition with penis enlargement advertisements. And while they may

well constitute the bulk of art writing, they are also its most

destitute strata, both in form and in content. It is thus an interesting

choice to focus on this as a sampling of art-speak, because it is not

exactly representative. Meanwhile, authoritative high-end art writing is

respectfully left to keep pontificating behind MIT Press paywalls.4

So what is the language used in the sample examined by Rule and

Levine? As the authors incontrovertibly prove, it is incorrect English.

This is shown by statistically comparing press releases against the

British National Corpus (BNC), a database of British English usage.

Unsurprisingly, this exposes the deviant nature of IAE, which derives,

the authors argue, from copious foreign—mainly Latin—elements, leftovers

from decades of mistranslated continental art theory. This creates a

bastardized language that Rule and Levine compare to pornography: “we

know it when we see it.” So, on the one hand, there is the BNC usage, or

normal English. On the other, there is IAE, deviant and pornographic.

Oh, and alienating too.

But who is it that is willingly writing porn here? According to Rule

and Levine, IAE is, or might be, spoken by an anonymous art student in

Skopje, at the Proyecto de Arte Contemporáneo Murcia in Spain, by Tania

Bruguera, and by interns at the Chinese Ministry of Culture.5

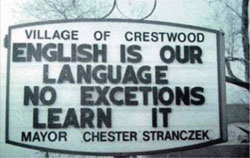

At this point I cannot help but ask: Why should an art student in

Skopje—or anyone else for that matter—conform to the British National

Corpus? Why should anyone use English words with the same frequency and

statistical distribution as the BNC? The only possible reason is that

the authors assume that the BNC is the unspoken measure of what English

is supposed to be: it is standard English, the norm. And this norm is to

be staunchly defended around the world.

As Mladen Stilinović told us a long time ago: an artist who cannot speak English is not an artist.6

This is now extended to gallery interns, curatorial graduate students,

and copywriters. And even within our beloved and seemingly global art

world, there is a Standard English Defence League at work, and the BNC

is its unspoken benchmark. Its norms are not only defined by grammar and

spelling, but also by an extremely narrow view of “incorrect English.”

As Aileen Derieg, one of the best translators of contemporary political

theory, has beautifully argued: “incorrect English” is anything “not

phrased in the simplest, shallowest terms, and the person reading it

can’t be bothered to make an effort to understand anything they don’t

already know.”7

In my experience, “correct” English writing is supposed to be as

plain and commonsensical as possible—and, unbelievably, people regard

this not as boring, but as a virtue. The climax of “correct” English art

writing is the standard contemporary art review, which is much too

afraid to say anything and often contents itself with rewriting press

releases in compliance with BNC norms. However, the main official rule

for standard English art writing is, in my own unsystematic statistical

analysis: never offend anyone more powerful than yourself. This rule is

followed perfectly in the IAE essay, which ridicules the fictive Balkan

art student who aggregates hapless bits of jargon in the hopes of

attracting interest from curators. Indeed, this probably happens every

day. But it’s such a cheap shot.

This is not to say that one shouldn’t constantly make fun of

contemporary art worlds and their preposterous taste, their pretentious

jargons and portentous hipsterisms. The art world (if such a thing even

exists) harbors a long tradition of terrific self-serving sarcasm. But

satire as one of the traditional tools of enlightenment is not only

defined by making fun. It gains its punch from who is being made fun of.

But Voltairean satire is mostly too risky. We are indeed lacking

authors attacking or even describing, in any language, the art world’s

jargon-veiled money laundering and post-democratic Ponzi schemes. Not

many people dare talk about post-mass-murder, gentrification-driven art

booms in, for example, Turkey or Sri Lanka. I certainly wouldn’t mind a

lot of statistical inquiry into these developments, whether in IAE or

Kurdish, satirical or serious.

But this is not Rule and Levine’s concern. Instead, they manage to

prove beyond a statistical doubt that IAE is deviant English. Fair

enough, but so what? And furthermore, doesn’t this verdict underestimate

the sheer wildness at work in the creation of new lingos? Alex Alberro

has demonstrated that advertising and promotion crucially created a

context for much early conceptual art in the 1960s.8

And today, the aggregate status of digitally circulated data is

wonderfully echoed in many so-called post-internet practices that

congenially mash up online commerce tools and itinerant JPEGs using (or

abusing) basic InDesign wrecking skills, creating fantastic crashes of

accelerated data sets within wacky circulation orbits. The intricacies,

undeniable fallacies, and joys of digital dispersion and circulation are

not, however, Rule and Levine’s focus. Nor are the politics of

translation and language. Their aim is to identify non-standard English

(or patronizingly praise it as involuntary poetry). But we should not

underestimate their analysis as just a nativist disdain for rambling

foreigners.

In an admirable essay, Mostafa Heddaya has pointed out the undeniable

complicity of IAE art jargon with political oppression in a multipolar

art world where contemporary art has become a must-have accessory for

tyrants and oligarchs.9

By highlighting the use of IAE to obfuscate and obscure massive

exploitation—such as the contested construction by New York University

and the Guggenheim of complexes on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi—Heddaya

makes an extremely important intervention in the debate.10

Whatever comes into the world through the global production and

dispersion of contemporary art is dripping from head to toe, from every

pore, with blood and dirt, to quote Karl Marx, another forerunner of

IAE. This certainly includes many instances of IAE, whose spread is

fueled, though by no means monopolized, by neo-feudal,

ultraconservative, and authoritarian contemporary art rackets. IAE is

not only the language of interns and non-native English speakers. It is

also a side effect of a renewed primitive accumulation operating

worldwide by means of art. IAE is an accurate expression of social and

class tensions around language and circulation within today’s art worlds

and markets: a site of conflict, struggle, contestation, and often

invisible and gendered labor. As such, it supports oppression and

exploitation. It legitimizes the use of contemporary art by the 1%. But

much like capitalism as such, it also enables a class and geographical

mobility whose restrictions are often blatantly defied by its users. It

creates a digital lingua franca, and through its glitches, it starts to

show the outlines of future publics that extend beyond preformatted

geographical and class templates. IAE can also be used to temporarily

expose some of the most glaring aspects of contemporary art’s dubious

financial involvements to a public beyond the confines of (often

unsympathetic) national forums. After all, IAE is also a language of dissidents, migrants, and renegades.

Again, none of this is of interest to Rule and Levine. Fair enough. I

doubt political economy matters much in the BNC. But their essay

perfectly expresses the backside of Heddaya’s argument. Because, as Rule

and Levine correctly state, after IAE has become too global to

intimidate anyone, the future lies in a return to conventional highbrow

English. And indeed, this is not a distant future, but the present, as

evidenced by a massive and growing academic industry monetizing and

monopolizing accepted uses of English. UK and US corporate academia has

one major advantage over the international education market: the ability

to offer (and police) proper English skills.

No gallery in Salvador da Bahia, no project space in Cairo, no

institution in Zagreb can opt out of the English language. And language

is and has always been a tool of Empire. For a native speaker, English

is a resource, a guarantee of universal access to employment in

countless places around the globe. Art institutions, universities,

colleges, festivals, biennales, publications, and galleries will usually

have American and British native speakers on their staff. Clearly, as

with any other resource, access needs to be restricted in order to

protect and perpetuate privilege. Interns and assistants the world over

must be told that their domestic—and most likely public—education simply

won’t do. The only way to shake off the shackles of your insufferable

foreign origins is to attend Columbia or Cornell, where you might learn

to speak impeccable English—untainted by any foreign accent or

non-native syntax. And after a couple of graduate programs where you pay

$34,740 annually for tuition, you just might be able to find yet

another internship.11

But here is my point: chances are you will be getting this education

on Saadiyat Island, where NYU is setting up a campus, whose allure for

paying customers resides in its ability to teach certified English to

non-native speakers. In relation to Heddaya’s argument, Frank Gehry’s

fortress will be paid for not only by exploiting Asian workers, but also

by selling “correct” English writing skills.

Or you might pay for this kind of education in Berlin, where UK and

US educational franchises, charging students seventeen thousand dollars a

year to learn proper English, have slowly started competing with the

city’s own admittedly lousy, inadequate, and provincial free art

schools.12

Or you might pay for such an education in countless already existing

franchises in China, where oppressive art speech will soon be delivered

in pristine BNC English. Old imperial privilege nestles quite

comfortably behind deconstructive oligarchic facades, and the policing

of “correct” English is the backside of IAE-facilitated neo-feudalism.

Such education will leave you indebted, because if you don’t pawn or

gamble your future on acquiring this skill, you will be shamed out of

the market for unpaid internships just because you aggregated some

critical theory that monolingual US-professors translated wrongly

decades ago. For the art student from Skopje, it’s no longer “publish or

perish.” It’s “pay or perish”!

That’s why I couldn’t care less when someone “unfolds his ideas,” or

engages in “questioning,” or in “collecting models of contemporary

realities.” Not everyone is lucky enough, or wealthy enough, to spend

years in private higher education. Convoluted as their wordsmithing may

be, press releases convey the sincere and often agonizing attempt by

wannabe predators to tackle a T. rex. And as Ana Teixeira Pinto has

said: nothing truly important can be said without wreaking havoc on the

rules of grammar.

Granted, IAE in its present state is rarely bold enough to do this.

It hasn’t gone far enough on any level. One reason is perhaps that it

took its ripping off of Latin (and other languages) too seriously. IAE

has clung to preposterous claims of erudition and has awed generations

of art students into dozing through Critical Studies seminars—even

though its status as aggregate spam is much more interesting.13

So we—the anonymous crowd of people (which includes myself) sustaining

and actually living this language—might want to alienate that language

even further, make it more foreign, and decisively cut its ties to any

imaginary original.

If IAE is to go further, its pretenses to Latin origins need to be

seriously glitched. And for a suggestion on how to do this, we need look

no further than the EDL’s ripped off slogan: Unus Mundas, Una Gens,

Unus Disco (One World, One Race, One Disco). Let’s ignore for a moment

that the word “disco” could sound so foreign that Rule and Levine might

sensibly suggest renaming it “platter playback shack.” Because actually

EDL’s slogan is hardly composed of Latin at all. Rather, it’s written in

IDL: International Disco Latin. It is a queer Latin made by splashing

mutant versions of gender across assumed nouns. It’s a language that

takes into account its digital dispersion, its composition and artifice.

This is the template for the language I would like to communicate in,

a language that is not policed by formerly imperial, newly global

corporations, nor by national statistics—a language that takes on and

confronts issues of circulation, labor, and privilege (or at least

manages to say something at all), a language that is not a luxury

commodity nor a national birthright, but a gift, a theft, an excess or

waste, made between Skopje and Saigon by interns and non-resident aliens

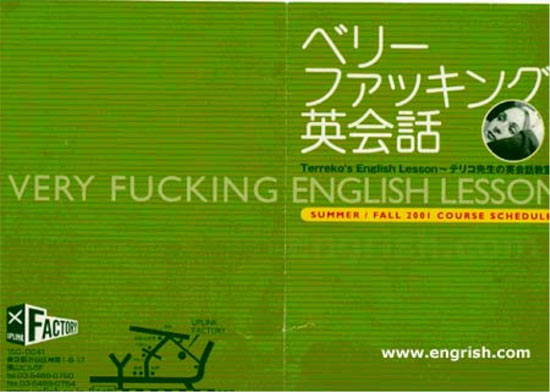

on Emoji keyboards. To opt for International Disco Latin also means

committing to a different form of learning, since disco also means “I

learn,” “I learn to know,” “I become acquainted with”—preferably with

music that includes heaps of accents. And for free. And in this

language, I will always prefer anus over bonus, oral over moral, Satin

over Latin, shag over shack. You’re welcome to call this pornographic,

discographic, alienating, or simply weird and foreign. But I suggest:

Let’s take a very fucking English lesson!

×

From e-flux.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario