As Google abandons its past, Internet archivists step in to save our collective memory

Google wrote its mission statement in 1999, a year after launch, setting the course for the company’s next decade:

“Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

For years, Google’s mission included the preservation of the past.

In

2001, Google made their first acquisition, the Deja archives. The

largest collection of Usenet archives, Google relaunched it as Google Groups, supplemented with archived messages going back to 1981.

In 2004, Google Books

signaled the company’s intention to scan every known book, partnering

with libraries and developing its own book scanner capable of digitizing

1,000 pages per hour.

In 2006, Google News Archive

launched, with historical news articles dating back 200 years. In 2008,

they expanded it to include their own digitization efforts, scanning

newspapers that were never online.

In

the last five years, starting around 2010, the shifting priorities of

Google’s management left these archival projects in limbo, or abandoned

entirely.

After a series of

redesigns, Google Groups is effectively dead for research purposes. The

archives, while still online, have no means of searching by date.

Google News Archives are dead, killed off in 2011, now directing searchers to just use Google.

Google Books is still online, but curtailed their scanning efforts in recent years, likely discouraged by a decade of legal wrangling still in appeal. The official blog stopped updating in 2012 and the Twitter account’s been dormant since February 2013.

Even Google Search, their flagship product, stopped focusing on the history of the web. In 2011, Google removed the Timeline view letting users filter search results by date, while a series of major changes to their search ranking algorithm increasingly favored freshness over older pages from established sources. (To the detriment of some.)

Two months ago, Larry Page said the company’s outgrown its 14-year-old mission statement. Its ambitions have grown, and its priorities have shifted.

Google

in 2015 is focused on the present and future. Its social and mobile

efforts, experiments with robotics and artificial intelligence,

self-driving vehicles and fiberoptics.

As

it turns out, organizing the world’s information isn’t always

profitable. Projects that preserve the past for the public good aren’t

really a big profit center. Old Google knew that, but didn’t seem to

care.

The desire to preserve the past died along with 20% time, Google Labs, and the spirit of haphazard experimentation.

Google may have dropped the ball on the past, but fortunately, someone was there to pick it up.

The Internet Archive

is mostly known for archiving the web, a task the San Francisco-based

nonprofit has tirelessly done since 1996, two years before Google was

founded.

The Wayback Machine now indexes over 435 billion webpages going back nearly 20 years, the largest archive of the web.

For most people, it ends there. But that’s barely scratching the surface.

Most don’t know that the Internet Archive also hosts:

- Books. One of the world’s largest open collections of digitized books, over 6 million public domain books, and an open library catalog.

- Videos. 1.9 million videos, including classic TV, 1,300 vintage home movies, and 4,000 public-domain feature films.

- The Prelinger Archives. Over 6,000 ephemeral films, including vintage advertising, educational and industrial footage.

- Audio. 2.3 million audio recordings, including over 74,000 radio broadcasts, 13,000 78rpm records, and 1.7 million Creative Commons-licensed audio recordings.

- Live music. Over 137,000 concert recordings, nearly 10,000 from the Grateful Dead alone.

- Audiobooks. Over 10,000 audiobooks from LibriVox and more.

- TV News. 668,000 news broadcasts with full-text search.

- Scanning services. Free and open access to scan complete print collections in 33 scanning centers, with 1,500 books scanned daily.

- Software. The largest collection of historical software in the world.

That last item, the software collection, may start to change public perception and awareness of the Internet Archive.

Spearheaded by archivist/filmmaker Jason Scott, the software preservation effort began on his own site in 2004 with a massive collection of shareware CD-ROMs from the BBS age.

After

he joined the Internet Archive as an employee, he started shoveling all

that vintage software onto their servers, along with software gathered

from historic FTP sites, shareware websites, tape archives, and anything else he could find.

But actually using

old software can be rough even for experienced geeks, often requiring a

maze of outdated archival utilities, obscure file formats, and

emulators to run.

In October 2011, Jason Scott wrote a call-to-arms aimed at making computer history accessible and ubiquitous — by porting classic systems to the browser.

“Without sounding too superlative, I think this will change computer history forever. The ability to bring software up and running into any browser window will enable instant, clear recall and reference of the computing experience to millions.”

Two years later, it was all real.

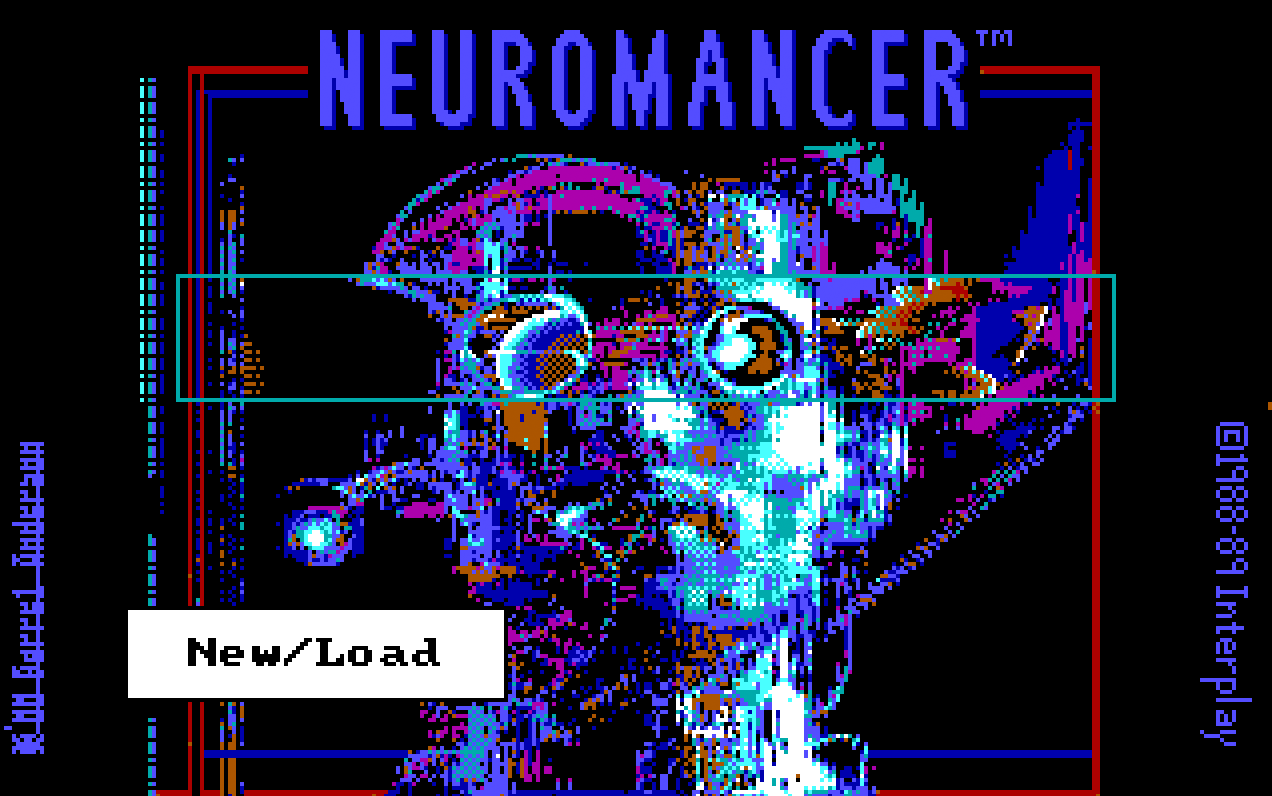

In October 2013, the Internet Archive tested the waters with the Historical Software Collection,

64 historic games and applications from computing history playable in

the browser. No installation required — just one click, and you were

trying out Spacewar! for the PDP-1, VisiCalc for the Apple II, or Pitfall for the Atari 2600.

By Christmas, they launched The Console Living Room, nearly 3,000 games from a dozen different consoles. Popular systems like the ColecoVision and Sega Genesis were represented, but also obscure and hard-to-find consoles like the Fairchild Channel F and Watara SuperVision.

A year later, they launched the Internet Arcade — hundreds of classic arcade games emulated with JSMAME, part of the JSMESS package.

Earlier this month, the Archive made headlines with the latest addition to its collection: nearly 2,300 vintage MS-DOS games, playable in the browser.

A technical breakthrough, the games are played on the popular DOSBox emulator, ported to Javascript by one brilliant, talented engineer.

The

experience of clicking a link and playing a game you haven’t seen in 25

years is magical, and many other people felt the same way.

News of the MS-DOS Game Collection got widespread media coverage, including The Washington Post, The Verge, and The Guardian, with thousands of people hitting the site every minute.

Millions

of people are discovering software they’ve never seen before, or

revisiting games from their past. People are making Let’s Play videos of

30-year-old games, played in a Chrome tab.

When

this launched, there were dozens of confused comments from people

wondering what old videogames has to do with Internet history.

In my mind, this stems from mistaken perception issues of the Internet Archive as solely an institution saving webpages.

But their mission and motto is much broader:

Universal access to all knowledge.

The Internet Archive is not Google.

The

Internet Archive is a chaotic, beautiful mess. It’s not well-organized,

and its tools for browsing and searching the wealth of material on

there are still rudimentary, but getting better.

But

this software emulation project feels, to me, like the kind of thing

Google would have tried in 2003. Big, bold, technically challenging, and

for the greater good.

This

effort is the perfect articulation of what makes the Internet Archive

great — with repercussions for the future we won’t fully appreciate for

years.

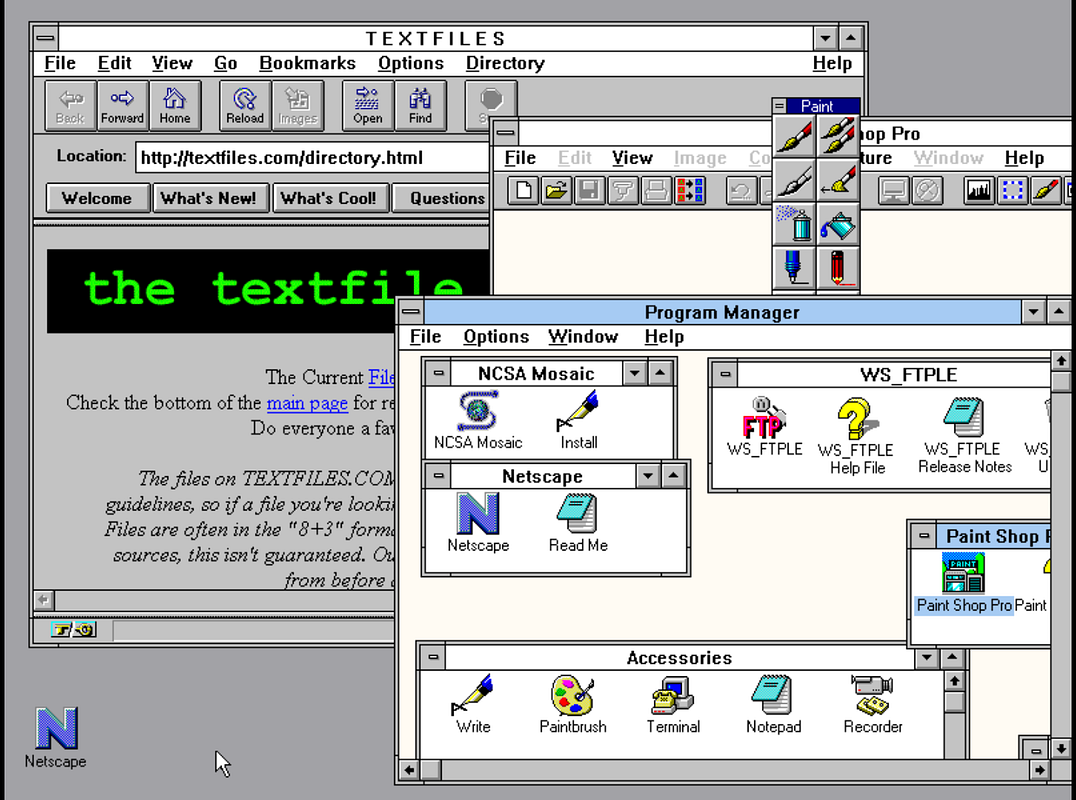

But here’s a glimpse: last week, one of the JSMESS developers managed to get Netscape running on Windows 3.1

with functional networking. All of computing history is within our

grasp, accessible from a single click, and this is the first step.

It’s not just about games — that’s just the hook.

It’s about preserving our digital history, which as we know now, is as easy to delete as 15 years of GeoCities.

We can’t expect for-profit corporations to care about the past, but we can support the independent, nonprofit organizations that do.

From here.

From here.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario