Harun Farocki, The Words of the Chairman (Die Worte des Vorsitzenden), 1967. 16mm, 3 minutes.

How to begin? The first sentence sets the scene. It is a building

block for a world to emerge in between words, sounds, and images. The

beginning of a text or film is a model of the whole—an anticipation.

A good beginning holds a problem in its most basic form. It looks effortless, but rarely is. A good beginning requires the precision and skill to say things simply. Like the crafts of making bricks, weapons, or files on hard drives, there is an art of creating beginnings.

One of Harun Farocki’s beginnings:

We can drop right into the middle of events.(1)

Harun Farocki’s legendary works—as filmmaker, writer, and organizer—are full of exemplary beginnings. From agitprop shorts to film essays and beyond. From didactic fiction to cinema verité. From single channel to multi-screen. From Kodak to .avi, from Mao to mashup. From silent films to hyperventilating talkies. From close reading to distanced comment. From interview to intervention, from collaboration to corroboration. On July 30, Harun Farocki died.

Over more than four decades, Farocki produced an extraordinary body of work that, for someone who continuously compared things, situations, and images to one another, is paradoxically incomparable. In all he did, he kept it simple, clear, and grounded. In cinematic terms: at eye level. His legacy spans generations, genres, and geographies. And the abundance of ideas and perspectives in his work does not cease to inspire. It trickles, disseminates, perseveres.

Farocki’s practice was not about perfecting one craft—it was rather about perfecting the art of inventing and adding new ones. Even when he became a master of his craft he didn’t stop. He just kept going. He became an eternal beginner. Had he lived another 25 years he might have started making Theremin films with bare hands, by focusing his mind, paying attention to the glitches of a new technology most probably developed for a stunning form of consumer oriented warfare.

How to begin, again?

In 1992, a title of one of Farocki’s texts makes a curious declaration: “Reality would have to begin.”(2) It implies that reality hasn’t even started. It is a puzzling statement indeed; especially from someone already considered an influential documentary filmmaker. Farocki suggests that reality might have to be brought about by resisting military infrastructure, its tools of vision and knowledge. But the quote also clearly declares that reality does not yet exist; at least not in any form that deserves the name. And let’s face it: Aren’t we still confronted with the same wretched impositions trying to pass as reality these days? Just now it’s being sweated over at Foxconn and sedimented on secret Snapchat servers: a Netflix soap featuring ISIS as teenage Deleuzian war machine. In earlier decades, Facebook might have been called Springer Press (not least in West Germany), ISIS called SA, and the USAF, well, USAF. The names of war change just as as war itself does. Reality’s absence stays put.

This beginning takes the form of a statement:

The hero is thrown into his world. The hero has no parents and no teachers. He has to learn by himself which roles are valid.(3)

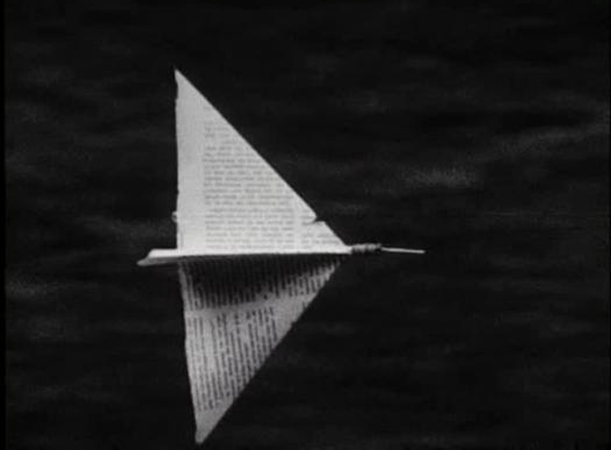

One of Farocki’s first films, The Words of the Chairman (Die Worte des Vorsitzenden), is a legendary agitprop short. A Mao bible is torn up, its pages folded into a paper airplane hurled at a Shah dummy. Words… argues that statements by authorities need to be messed with and set in motion. Texts and images must be used unexpectedly, tossed into the world—both commandeered and set free. Settings, views, and attitudes taken for granted have to be rigorously dissected, torn apart, reconfigured. There are no teachers or parents to lead the way. Throughout Farocki’s work, conflict will continue to manifest in mundane objects and situations.(4) In this case, a simple sheet of paper. Conflict is not only part of the content, but also of the production setting. Worte des Vorsitzenden is made in collaboration with both Otto Schily—later to become German interior minister—and Holger Meins, who died in a prison hunger strike as a member of the Red Army Faction. One would become the face of the state, the other would die as its enemy. Production holds conflict. It is its most basic form.

Another beginning:

Does the world exist, if I am not watching it?(5)

This beginning is among his last: it is part of the brilliant series Paralell I–IV dealing with computer generated game-imagery. This series reflects on elements of game worlds, on polygons, NPC’s, 8-bit graphics, arse physics and unilateral surfaces. Ok, I made up the arse physics, sorry. Paralell I–IV sketches the first draft of a history of computer generated images that is still emerging as we speak. It skims the surfaces of virtual worlds and coolly scans their glitches. Paralell I–IV is so humble, so concise, so charming and bloody fantastic that I could go on about it for hours. You are so lucky it hasn’t got arse physics or else I would.

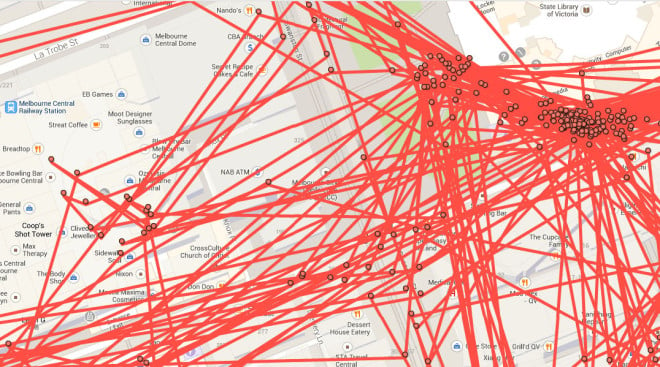

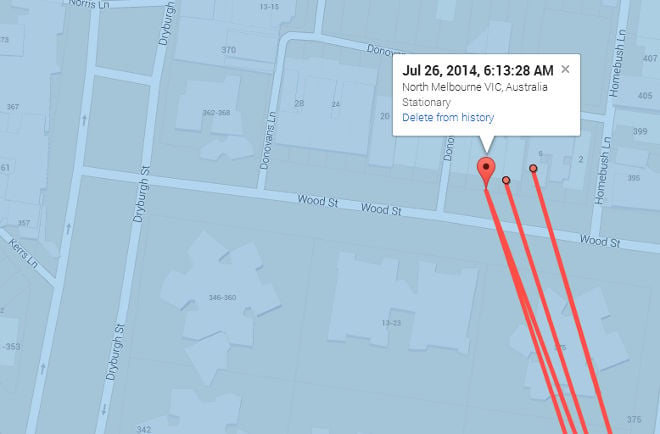

In 1992, Videograms of a Revolution, codirected with Andrei Ujică, captured a similar moment of emergence. The seminal work compiles material from over 125 hours of TV broadcasts and amateur footage of the ’89 Romanian uprisings. It demonstrates how TV stops recording reality and starts creating it instead. Videograms asks: Why did insurgents not storm the presidential palace, but the TV station? At the very moment the social revolution of 1917 ended irrevocably, a new and equally ambivalent technological revolution took place. People ask for bread: they end up with camcorders. TV studios host revolts. Reality is created by representation(6)—Farocki, Flusser, and others were among the first to report this sea change as it happened. As things become visible, they also become real. Protesters jump through TV screens and spill out onto streets. This is because the surface of the screen is broken: content can no longer be contained when protest, rare animals, breakfast cereals, prime time, and TV test patterns escape the flatness of 2D representation.(7) In 1989, protesters storm TV stations. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee invents the World Wide Web. Twenty-five years later, oligarchs start to ask: If people don’t have bread, why don’t they eat their browsers instead?

These works are building blocks. One can start building now. But what, exactly? Farocki starts building parallels. Shot on left monitor, countershot to the right. Montage arranged as solid bricks of spatialized narration. On the Construction of Griffith’s Films uses Hantarex cubes as construction material. Cinema is now rephrased as architecture.(8)

There used to be one TV per flat. Now there are many. Political systems dwindle; screens multiply. Workers Leaving the Factory begins several times: a perfect grammar of cinema’s spatial turn.(9) The first version of the work is single screen. The second version turns into twelve monitors simultaneously playing workers leaving the factory in different periods of twentieth century film history.(10) Dialectics explodes into dodecalectics. Farocki multiplies the exits and the worlds of labor multiply in turn. Workers leave the factory to become actors—and to play themselves. Factories turn into theaters of operation. From 1987 on, Farocki also filmed how work puts on a show by way of exhibition. More than a dozen cinema verité films exhibit training, pitches, meetings, people striving to perform: The Appearance, The Interview, Nothing Ventured.(11) People pitch campaigns and projects as if their life depends on it. The staging of labor precedes commodity infatuation. The Leading Role (Die Führende Rolle, 1994) shows the design of GDR May Day parades while the Berlin wall was already crumbling. Think of a televised ballet performed by a fantasy military sports brigade.

Another group of works investigates how buildings train bodies, reflexes, and perception. A prison: how to lock up by looking; a shopping mall: how to choreograph clients; brick factories around the world: how to make bricks manually, by machine, and through 3D printing.(12) This was the plan at least. The 3D printed bricks didn’t make it into the film after all—the technology was too slow to keep up with Farocki’s furious pace.

In its inception, parallel montage arose alongside conveyor belts—an industrial form of production across different locations arranged one after another. Its spatial turn arrived with major transformations: deindustrialization. Labor as spectacle. Factories turned museums. Conveyor belts dismantled and reinstalled in China, where mega-museums rise in parallel. Production persists in worlds split off by one-way mirrors. Surfaces glisten, spaces disconnect amongst commodity addiction, cheap airfare, and attention deficit: the new normal. Farocki looks, listens, demonstrates, aligns. At one point, he goes quiet. Respite(13) has no soundtrack whatsoever. In the video, Farocki shows silent footage extorted from a detainee at Westerbork deportation camp for purposes of Nazi infotainment. He peels away the staging of normalcy covering genocide layer by layer. The absence of sound is the film’s most striking documentary layer; it records the silence of the audience that took Nazi stagecraft for reality.

Reality would have to begin.

Another of Farocki’s beginnings:

Looks like it might have just been a glitch.(14)

A soldier drives a tank through a virtual landscape. After asymmetrical US warfare in Vietnam, the ongoing Cold War of the ’80s has given way to a permanent asymmetrical war against “Terror.” War has changed. It also remains the same. In the twentieth century, Farocki suggests resisting a military reconnaissance that uses analog aerial photography. In the twenty-first century, Farocki observes armies that rely on simulations. Photography records a present situation. Simulations rehearse a future to be. They push out representations and make worlds, pixel by pixel, bit by bit—building by destruction and subtraction. Cameras do not only record, they also track and guide. They scan and project. They seek and destroy. War has changed. It also has remained the same: complicit with business interests, deeply entrenched within the most mundane details of everyday reality—now generated by images.

Like warfare, Farocki’s work has changed. Like warfare, it has remained the same. Harun’s latest works were always the most advanced, pushing the edge of analysis and vision. One can’t afford nostalgia when dealing with the tools of permanent workfare: transmission, rephrasing, modeling. Like in Words of the Chairman when a page of paper is folded to become a weapon. The printed page has turned into a set of polygons. It can be folded into fighter jets, runway handbags, or furry Disney creatures. They could be part of education, games, or military operations. Just like the paper airplane, by the way.

In an interview published after his death, Farocki says of Words of the Chairman:

“It was about a utopian moment suddenly projected into the world. One couldn’t see it in the outside world; at least one couldn’t record it with a camera. And in this case—and I still feel this way—I was able to produce an entirely artificial world, something like a 3D animation.”(15)

Filmmakers have hitherto only represented the world in various ways; the point is to generate worlds differently.

Paradoxically the beginning is also often the last part to be created, since it has to anticipate everything. But Farocki’s late works are not just new versions of old beginnings. They started smiling. The late works radiated playfulness not in spite of their profoundness or seriousness but precisely because of it: from Serious Games to just games. From Deep Play to play proper. They also became more relevant and exciting by the minute. Farocki got closer to the beginner’s spirit day by day.

Today, workers are leaving the factory to play Metal Gear Solid in the parking lot. They got confused because the disco grid installed for office raves was hacked and now shows ISIS fashion week ads.(16) Today workers are players, proxies, pitchers, soldiers, dancers, spammers, bots, and refugees. Ballistics is upgraded with arse physics. TVs are built with Minecraft blocks. Reality is still missing in action. Harun’s work is more necessary than ever and I am gutted that he is no longer here.

I know I am not alone in this. From Berlin to Beirut to Kolkata, Mexico, Gwangju, and wherever airlines and wi-fi travel, Harun’s work struck a chord and brought people together: from Straub and Huillet nerds to Tumblr impressionists and drone opponents. From West Berlin to the West Bank. From salon bolsheviks, dialup activists, and SketchUp gallerinas. From portable film clubs to mobile phone browsers. I personally know at least one militia member who was floored by his work. Harun was his own UN smoking lounge in an imaginary corridor shared by the offices of the technology, Security Council, soccer, and moving image subcommittees. His work lives on invincible; his convertible is killing it still. People faint every time it comes down Karl-Marx-Allee.(17)

All of us are now in a position to answer your question:

Does the world exist, if I am not watching it?(18)

Reality would first have to begin. And perhaps, by beginning over and over again, reality can finally be brought about.

Note:

This text is written in the mode of fan prose. Of all Farocki’s 120 or so moving image works, I have seen only about two thirds. People who have written on his work with expertise, lucidity, and insight include Thomas Elsaesser, Christa Blümlinger, Tilman Baumgärtel, Nora Alter, Georges Didi-Huberman, Olaf Möller, Volker Pantenburg, Tom Keenan, and many others. Please read their writings for a comprehensive overview of Harun Farocki’s body of work spanning almost five decades. For biographical background please watch Anna Faroqhi’s outstanding short video that gives a most beautiful account: A Common Life (Ein gewöhnliches Leben) (2006–07, 26 minutes). Thank you to Harun Farocki’s longtime collaborator Matthias Rajmann for providing instant access to online downloads.

(1) Parallel II, 2014. One-channel video installation, color, sound, 9 minutes.

(2) Harun Farocki, “Reality Would Have to Begin,” Imprint: Writings / Nachdruck: Texte, ed. Susanne Gaensheimer and Nicolaus Schafhausen (New York: Lukas & Sternberg; Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2001), 186–213 →

(3) Parallel IV, 2014. One-channel video installation, color, sound, 11 minutes.

(4) There is a strong parallel to Martha Rosler’s work Bringing The War Home, made in the same year, which also insists on the domesticity and ubiquity of warfare.

(5) From Parallel I, 2012. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 16 minutes.

(6) This work is preceded by “Ein Bild,” a conversation with Vilem Flusser about a cover of Bild Zeitung. Also, obviously reality has always been created by representations to an extent, but this period marks the emergence of reality being created by digital imagery.

(7) At some point during the stampede cinema becomes a casualty too. It ceases to be a place where production condenses social conflict.

(8) On the Construction of Griffith’s Films (Zur Bauweise des Films bei Griffith), 2006. Two-channel video installation, black and white, 8 minutes.

(9) Workers Leaving the Factory (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik), 1995. Digital video, sound, 36 minutes. Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik in elf Jahrzehnten), 2006. Twelve-channel video installation, 36 minutes.

(10) Another version is installed in Essen right now, showing actual workers leaving factories in fifteen different countries, as part of the work Labour in a Single Shot codirected with Antje Ehmann. I haven’t seen it yet.

(11) The Appearance (Der Auftritt), 1996. Video, sound, 40 minutes; The Interview (Die Bewerbung), 1997. Video, sound, 58 minutes; Nothing Ventured (Nicht ohne Risiko), 2004. Video, sound, 50 minutes.

(12) I Thought I was Seeing Convicts (Ich glaubte Gefangene zu sehen), 2000. Video, sound, 60 minutes; The Creators of Shopping Worlds (Die Schöpfer der Einkaufswelten), 2001. Video, sound, 72 minutes; In Comparison (Im Vergleich), 2009. Video, sound, 60 minutes.

(13) Respite (Der Aufschub), 2007. Video, sound, 38 minutes.

(14) From Serious Games I: Watson is Down. 2010. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 8 minutes.

(15) Philipp Goll, “Harun Farocki: Ein posthum erscheinendes Interview über Fußball, Mao und das Filmemachen,” Jungle World no. 32 (August 2014) →

(16) A reference to recent conversations with Brian Kuan Wood and Andrew Norman Wilson’s work, Sone →

(17) Harun’s Volvo cabrio might have singlehandedly saved the GDR if strategically deployed at May Day parades.

(18) From Parallel I, 2012. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 16 minutes.

A good beginning holds a problem in its most basic form. It looks effortless, but rarely is. A good beginning requires the precision and skill to say things simply. Like the crafts of making bricks, weapons, or files on hard drives, there is an art of creating beginnings.

One of Harun Farocki’s beginnings:

We can drop right into the middle of events.(1)

Harun Farocki’s legendary works—as filmmaker, writer, and organizer—are full of exemplary beginnings. From agitprop shorts to film essays and beyond. From didactic fiction to cinema verité. From single channel to multi-screen. From Kodak to .avi, from Mao to mashup. From silent films to hyperventilating talkies. From close reading to distanced comment. From interview to intervention, from collaboration to corroboration. On July 30, Harun Farocki died.

Over more than four decades, Farocki produced an extraordinary body of work that, for someone who continuously compared things, situations, and images to one another, is paradoxically incomparable. In all he did, he kept it simple, clear, and grounded. In cinematic terms: at eye level. His legacy spans generations, genres, and geographies. And the abundance of ideas and perspectives in his work does not cease to inspire. It trickles, disseminates, perseveres.

Farocki’s practice was not about perfecting one craft—it was rather about perfecting the art of inventing and adding new ones. Even when he became a master of his craft he didn’t stop. He just kept going. He became an eternal beginner. Had he lived another 25 years he might have started making Theremin films with bare hands, by focusing his mind, paying attention to the glitches of a new technology most probably developed for a stunning form of consumer oriented warfare.

How to begin, again?

In 1992, a title of one of Farocki’s texts makes a curious declaration: “Reality would have to begin.”(2) It implies that reality hasn’t even started. It is a puzzling statement indeed; especially from someone already considered an influential documentary filmmaker. Farocki suggests that reality might have to be brought about by resisting military infrastructure, its tools of vision and knowledge. But the quote also clearly declares that reality does not yet exist; at least not in any form that deserves the name. And let’s face it: Aren’t we still confronted with the same wretched impositions trying to pass as reality these days? Just now it’s being sweated over at Foxconn and sedimented on secret Snapchat servers: a Netflix soap featuring ISIS as teenage Deleuzian war machine. In earlier decades, Facebook might have been called Springer Press (not least in West Germany), ISIS called SA, and the USAF, well, USAF. The names of war change just as as war itself does. Reality’s absence stays put.

This beginning takes the form of a statement:

The hero is thrown into his world. The hero has no parents and no teachers. He has to learn by himself which roles are valid.(3)

One of Farocki’s first films, The Words of the Chairman (Die Worte des Vorsitzenden), is a legendary agitprop short. A Mao bible is torn up, its pages folded into a paper airplane hurled at a Shah dummy. Words… argues that statements by authorities need to be messed with and set in motion. Texts and images must be used unexpectedly, tossed into the world—both commandeered and set free. Settings, views, and attitudes taken for granted have to be rigorously dissected, torn apart, reconfigured. There are no teachers or parents to lead the way. Throughout Farocki’s work, conflict will continue to manifest in mundane objects and situations.(4) In this case, a simple sheet of paper. Conflict is not only part of the content, but also of the production setting. Worte des Vorsitzenden is made in collaboration with both Otto Schily—later to become German interior minister—and Holger Meins, who died in a prison hunger strike as a member of the Red Army Faction. One would become the face of the state, the other would die as its enemy. Production holds conflict. It is its most basic form.

Another beginning:

Does the world exist, if I am not watching it?(5)

This beginning is among his last: it is part of the brilliant series Paralell I–IV dealing with computer generated game-imagery. This series reflects on elements of game worlds, on polygons, NPC’s, 8-bit graphics, arse physics and unilateral surfaces. Ok, I made up the arse physics, sorry. Paralell I–IV sketches the first draft of a history of computer generated images that is still emerging as we speak. It skims the surfaces of virtual worlds and coolly scans their glitches. Paralell I–IV is so humble, so concise, so charming and bloody fantastic that I could go on about it for hours. You are so lucky it hasn’t got arse physics or else I would.

In 1992, Videograms of a Revolution, codirected with Andrei Ujică, captured a similar moment of emergence. The seminal work compiles material from over 125 hours of TV broadcasts and amateur footage of the ’89 Romanian uprisings. It demonstrates how TV stops recording reality and starts creating it instead. Videograms asks: Why did insurgents not storm the presidential palace, but the TV station? At the very moment the social revolution of 1917 ended irrevocably, a new and equally ambivalent technological revolution took place. People ask for bread: they end up with camcorders. TV studios host revolts. Reality is created by representation(6)—Farocki, Flusser, and others were among the first to report this sea change as it happened. As things become visible, they also become real. Protesters jump through TV screens and spill out onto streets. This is because the surface of the screen is broken: content can no longer be contained when protest, rare animals, breakfast cereals, prime time, and TV test patterns escape the flatness of 2D representation.(7) In 1989, protesters storm TV stations. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee invents the World Wide Web. Twenty-five years later, oligarchs start to ask: If people don’t have bread, why don’t they eat their browsers instead?

These works are building blocks. One can start building now. But what, exactly? Farocki starts building parallels. Shot on left monitor, countershot to the right. Montage arranged as solid bricks of spatialized narration. On the Construction of Griffith’s Films uses Hantarex cubes as construction material. Cinema is now rephrased as architecture.(8)

There used to be one TV per flat. Now there are many. Political systems dwindle; screens multiply. Workers Leaving the Factory begins several times: a perfect grammar of cinema’s spatial turn.(9) The first version of the work is single screen. The second version turns into twelve monitors simultaneously playing workers leaving the factory in different periods of twentieth century film history.(10) Dialectics explodes into dodecalectics. Farocki multiplies the exits and the worlds of labor multiply in turn. Workers leave the factory to become actors—and to play themselves. Factories turn into theaters of operation. From 1987 on, Farocki also filmed how work puts on a show by way of exhibition. More than a dozen cinema verité films exhibit training, pitches, meetings, people striving to perform: The Appearance, The Interview, Nothing Ventured.(11) People pitch campaigns and projects as if their life depends on it. The staging of labor precedes commodity infatuation. The Leading Role (Die Führende Rolle, 1994) shows the design of GDR May Day parades while the Berlin wall was already crumbling. Think of a televised ballet performed by a fantasy military sports brigade.

Another group of works investigates how buildings train bodies, reflexes, and perception. A prison: how to lock up by looking; a shopping mall: how to choreograph clients; brick factories around the world: how to make bricks manually, by machine, and through 3D printing.(12) This was the plan at least. The 3D printed bricks didn’t make it into the film after all—the technology was too slow to keep up with Farocki’s furious pace.

In its inception, parallel montage arose alongside conveyor belts—an industrial form of production across different locations arranged one after another. Its spatial turn arrived with major transformations: deindustrialization. Labor as spectacle. Factories turned museums. Conveyor belts dismantled and reinstalled in China, where mega-museums rise in parallel. Production persists in worlds split off by one-way mirrors. Surfaces glisten, spaces disconnect amongst commodity addiction, cheap airfare, and attention deficit: the new normal. Farocki looks, listens, demonstrates, aligns. At one point, he goes quiet. Respite(13) has no soundtrack whatsoever. In the video, Farocki shows silent footage extorted from a detainee at Westerbork deportation camp for purposes of Nazi infotainment. He peels away the staging of normalcy covering genocide layer by layer. The absence of sound is the film’s most striking documentary layer; it records the silence of the audience that took Nazi stagecraft for reality.

Reality would have to begin.

Another of Farocki’s beginnings:

Looks like it might have just been a glitch.(14)

A soldier drives a tank through a virtual landscape. After asymmetrical US warfare in Vietnam, the ongoing Cold War of the ’80s has given way to a permanent asymmetrical war against “Terror.” War has changed. It also remains the same. In the twentieth century, Farocki suggests resisting a military reconnaissance that uses analog aerial photography. In the twenty-first century, Farocki observes armies that rely on simulations. Photography records a present situation. Simulations rehearse a future to be. They push out representations and make worlds, pixel by pixel, bit by bit—building by destruction and subtraction. Cameras do not only record, they also track and guide. They scan and project. They seek and destroy. War has changed. It also has remained the same: complicit with business interests, deeply entrenched within the most mundane details of everyday reality—now generated by images.

Like warfare, Farocki’s work has changed. Like warfare, it has remained the same. Harun’s latest works were always the most advanced, pushing the edge of analysis and vision. One can’t afford nostalgia when dealing with the tools of permanent workfare: transmission, rephrasing, modeling. Like in Words of the Chairman when a page of paper is folded to become a weapon. The printed page has turned into a set of polygons. It can be folded into fighter jets, runway handbags, or furry Disney creatures. They could be part of education, games, or military operations. Just like the paper airplane, by the way.

In an interview published after his death, Farocki says of Words of the Chairman:

“It was about a utopian moment suddenly projected into the world. One couldn’t see it in the outside world; at least one couldn’t record it with a camera. And in this case—and I still feel this way—I was able to produce an entirely artificial world, something like a 3D animation.”(15)

Filmmakers have hitherto only represented the world in various ways; the point is to generate worlds differently.

Paradoxically the beginning is also often the last part to be created, since it has to anticipate everything. But Farocki’s late works are not just new versions of old beginnings. They started smiling. The late works radiated playfulness not in spite of their profoundness or seriousness but precisely because of it: from Serious Games to just games. From Deep Play to play proper. They also became more relevant and exciting by the minute. Farocki got closer to the beginner’s spirit day by day.

Today, workers are leaving the factory to play Metal Gear Solid in the parking lot. They got confused because the disco grid installed for office raves was hacked and now shows ISIS fashion week ads.(16) Today workers are players, proxies, pitchers, soldiers, dancers, spammers, bots, and refugees. Ballistics is upgraded with arse physics. TVs are built with Minecraft blocks. Reality is still missing in action. Harun’s work is more necessary than ever and I am gutted that he is no longer here.

I know I am not alone in this. From Berlin to Beirut to Kolkata, Mexico, Gwangju, and wherever airlines and wi-fi travel, Harun’s work struck a chord and brought people together: from Straub and Huillet nerds to Tumblr impressionists and drone opponents. From West Berlin to the West Bank. From salon bolsheviks, dialup activists, and SketchUp gallerinas. From portable film clubs to mobile phone browsers. I personally know at least one militia member who was floored by his work. Harun was his own UN smoking lounge in an imaginary corridor shared by the offices of the technology, Security Council, soccer, and moving image subcommittees. His work lives on invincible; his convertible is killing it still. People faint every time it comes down Karl-Marx-Allee.(17)

All of us are now in a position to answer your question:

Does the world exist, if I am not watching it?(18)

Reality would first have to begin. And perhaps, by beginning over and over again, reality can finally be brought about.

Note:

This text is written in the mode of fan prose. Of all Farocki’s 120 or so moving image works, I have seen only about two thirds. People who have written on his work with expertise, lucidity, and insight include Thomas Elsaesser, Christa Blümlinger, Tilman Baumgärtel, Nora Alter, Georges Didi-Huberman, Olaf Möller, Volker Pantenburg, Tom Keenan, and many others. Please read their writings for a comprehensive overview of Harun Farocki’s body of work spanning almost five decades. For biographical background please watch Anna Faroqhi’s outstanding short video that gives a most beautiful account: A Common Life (Ein gewöhnliches Leben) (2006–07, 26 minutes). Thank you to Harun Farocki’s longtime collaborator Matthias Rajmann for providing instant access to online downloads.

(1) Parallel II, 2014. One-channel video installation, color, sound, 9 minutes.

(2) Harun Farocki, “Reality Would Have to Begin,” Imprint: Writings / Nachdruck: Texte, ed. Susanne Gaensheimer and Nicolaus Schafhausen (New York: Lukas & Sternberg; Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2001), 186–213 →

(3) Parallel IV, 2014. One-channel video installation, color, sound, 11 minutes.

(4) There is a strong parallel to Martha Rosler’s work Bringing The War Home, made in the same year, which also insists on the domesticity and ubiquity of warfare.

(5) From Parallel I, 2012. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 16 minutes.

(6) This work is preceded by “Ein Bild,” a conversation with Vilem Flusser about a cover of Bild Zeitung. Also, obviously reality has always been created by representations to an extent, but this period marks the emergence of reality being created by digital imagery.

(7) At some point during the stampede cinema becomes a casualty too. It ceases to be a place where production condenses social conflict.

(8) On the Construction of Griffith’s Films (Zur Bauweise des Films bei Griffith), 2006. Two-channel video installation, black and white, 8 minutes.

(9) Workers Leaving the Factory (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik), 1995. Digital video, sound, 36 minutes. Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik in elf Jahrzehnten), 2006. Twelve-channel video installation, 36 minutes.

(10) Another version is installed in Essen right now, showing actual workers leaving factories in fifteen different countries, as part of the work Labour in a Single Shot codirected with Antje Ehmann. I haven’t seen it yet.

(11) The Appearance (Der Auftritt), 1996. Video, sound, 40 minutes; The Interview (Die Bewerbung), 1997. Video, sound, 58 minutes; Nothing Ventured (Nicht ohne Risiko), 2004. Video, sound, 50 minutes.

(12) I Thought I was Seeing Convicts (Ich glaubte Gefangene zu sehen), 2000. Video, sound, 60 minutes; The Creators of Shopping Worlds (Die Schöpfer der Einkaufswelten), 2001. Video, sound, 72 minutes; In Comparison (Im Vergleich), 2009. Video, sound, 60 minutes.

(13) Respite (Der Aufschub), 2007. Video, sound, 38 minutes.

(14) From Serious Games I: Watson is Down. 2010. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 8 minutes.

(15) Philipp Goll, “Harun Farocki: Ein posthum erscheinendes Interview über Fußball, Mao und das Filmemachen,” Jungle World no. 32 (August 2014) →

(16) A reference to recent conversations with Brian Kuan Wood and Andrew Norman Wilson’s work, Sone →

(17) Harun’s Volvo cabrio might have singlehandedly saved the GDR if strategically deployed at May Day parades.

(18) From Parallel I, 2012. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 16 minutes.